Abstract. This article justifies structural, systemic, and functional requirements for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations based on an analysis of their assigned combat missions across a variety of scenarios and defines current trends of its development in the immediate and long term.

Throughout human history, wars and armed conflicts have been unavoidable phenomena that significantly impact all areas of social life and even the fate of countries and peoples. Warring parties create military units to wage them − from small bands and squads in ancient times to regular armies numbering many thousands of soldiers in modern times. Their size and structure vary, depending primarily on the states’ ability to allocate the necessary mobilization resources, as well as on the military operations’ goals and objectives.

The 20th century saw more than a hundred military conflicts of varying duration and scale, but the two world wars left the deepest mark on the lives of peoples and had very severe consequences for many of the warring nations. In present-day conditions, the probability of a global, large-scale war is low, because it would likely be catastrophic due to the coalitions of states possessing highly destructive weapons, including weapons of mass destruction (WMD). However, the probability of such an international situation also cannot be ruled out entirely.

As the events of the late 20th and early 21st centuries show, the most realistic scenario under modern conditions includes the emergence of regional and local wars and armed conflicts in which the broad use of tactical-level combined-arms formations equipped with high-tech weapons, military and specialized equipment (WMSE) and utilizing effective forms, methods and techniques of warfare1 would play a leading and sometimes decisive role in achieving victory.

In this connection, determining the most important requirements for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations and prospects for its development in order to improve the ability to successfully perform combat missions acquires particular urgency in present and future military conflicts.

A military formation is a generalized term for bodies of troops, military subunits, detachments, forces, and other structural units of the armed forces, as well as other troops, that have a mission, an organizational structure, a prescribed strength, and a procedure for performing missions.

In the Ground Forces, tactical-level combined-arms formations include military units from a motorized rifle squad to a motorized rifle (tank) division. They also include military units and subunits of other branches and specialized forces. The organizational structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations provides an optimal combination of personnel numbers and WMSE to maintain their high combat readiness as well as ability to successfully conduct combat actions (operations) in different environments.

This article considers requirements for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations of upper hierarchical order – i.e., the motorized-rifle/tank division/brigade and equivalent military bases that are considered combined-arms formations and organizationally include military units and subunits up to the motorized rifle/tank platoon/company. In this case, most of the requirements are also true for the organizational and staff structure of lower-order tactical-level combined-arms formations.

One approach to determining the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations traditionally involves creating a rigid structure with stable links between its elements. An alternative solution is a modular structure that allows the formation of combat tactical groups depending on the specific situation. Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages.

A permanent organizational and staff structure ensures maximum controllability and predictability of unit actions. In peacetime, it facilitates more purposeful organization of unit qualitative combat training on the basis of unified programs, rapid introduction of advanced training methods and rational use of the material and technical base. However, this type of organizational and staff structure is not always acceptable in present-day warfare, especially in local (focal) armed conflicts that lack a continuous contact line, when the situation requires forming combined tactical groups.

Conversely, the modular organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations is more flexible, allowing for a much more rational use of available forces and assets, an adequate response to changes in the combat situation, as well as increased autonomy for heterogeneous tactical groups and the rapid creation of necessary combat systems from ready-made “modules” of different hierarchical affiliation.

The definition of the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations is substantially influenced by the military and economic potential of the state, the composition and capabilities of a particular potential adversary, the terms of preparation for military conflict action, as well as the content of characteristic tactical tasks assigned to tactical-level combined-arms formations in different environments (see Table).

Table

Primary Tactical Missions Assigned to Tactical-Level Combined-Arms Formations

| Environment | Missions assigned to tactical-level combined-arms formations |

| In times of peace | • maintaining combat readiness • ensuring quality combat training of troops • helping border troops provide national border security • preparing for territorial defense activities • assisting other troops (forces) in performing missions to protect and defend state property and airspace, the coast, and economic zones • assisting the population in emergency situations • combating terrorism inside and outside the Russian Federation • working with the military units of other Armed Forces branches, ministries, and departments to suppress preparations for military aggression against the Russian Federation • improving the mobilization deployment base • participating in information warfare • protecting Russia’s national interests on the territory of allies and other states on the basis of treaties • participating in peacekeeping (reconstruction) operations, etc.2,3 • participating in covering the strategic deployment of the Armed Forces and repelling aerospace attacks, launching massive fire strikes, disrupting troop and weapon control systems, and confusing enemy intelligence and electronic warfare • attacking the aggressor and joint fighting with the forces of allied nations • preventing the advancement of enemy tactical forces • ensuring the timely deployment of strategic reserves • destroying landing parties, enemy sabotage and reconnaissance groups, and illegal armed groups • eliminating the enemy’s breakthrough forces |

| In an armed conflict on the territory of other states, in local, regional, and large-scale wars | • restoring lost positions in the most important operational areas • participating in airborne, amphibious, and other joint operations by Armed Forces branches • defeating enemy air assets in the area of friendly forces • protecting and defending critical assets in the combat zone • ensuring the delivery of personnel, ammunition, and materiel • maintaining lines and areas in tactical and immediate operational depth • conducting defensive and offensive operations as part of the first and second echelons, and performing combined-arms reserve missions • replacing combined-arms formations that have lost combat effectiveness • covering the flanks of the task force • conducting combat actions (operations) as part of the operational and mobile reserve, etc.4,5,6 |

| When conducting territorial defense | • protecting and defending important military, government, and special facilities • combating sabotage and reconnaissance formations of foreign states and illegal armed groups • ensuring the delivery of humanitarian aid • participating in maintaining martial law • ensuring the passage of troops, including protecting and defending communications, equipping traffic routes, providing materiel, conducting evacuations, imposing curfews, etc.7,8 |

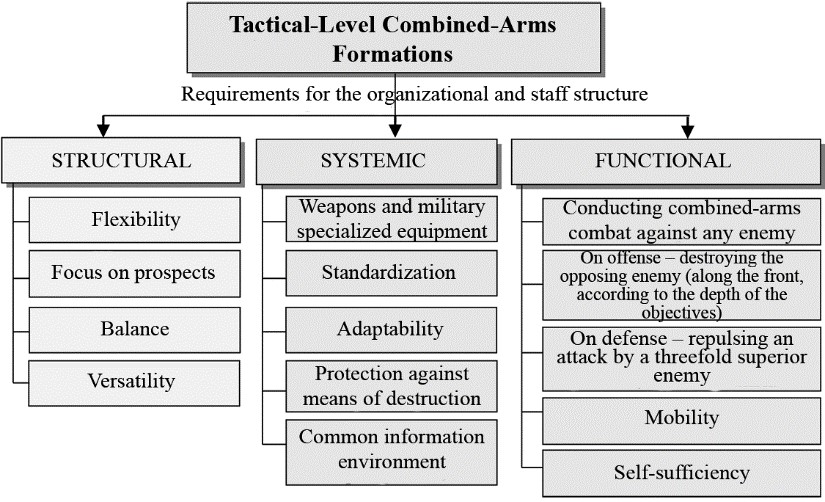

A comprehensive analysis of the essence of the tasks mentioned in the Table makes it possible to formulate modern structural, systemic and functional requirements for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Main requirements for the organizational and staff structure

of tactical-level combined-arms formations

The following section will more closely examine the requirements for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations presented in the Figure.

Structural Requirements

Flexibility. The organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations entails the ability to quickly form tactical combat groups of various purposes, compositions, and size to conduct combat actions (operations) depending on the emerging combat situation in the first echelon, second echelon, combined-arms reserve, or enveloping groups, raiding teams, advance and special detachments, and tactical airborne assault landings. In addition to motorized rifle and tank units, they may include military formations of missile forces and artillery, army aviation, air defense forces and assets, ground and air reconnaissance, electronic suppression, engineer troops, as well as units that ensure the use of military robotechnical systems, precision weapons, weapons based on new physical principles and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV).

Focus on prospects means the feasibility of the rapid optimization of the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations as applied to the conditions of a particular military conflict of varying intensity for carrying out successful combat operations against any adversary. Compliance with this requirement makes it possible, in our opinion, to avoid the hopeless practice of hurriedly creating combined formations in the form of divisional, regimental and battalion tactical groups, as well as creating combined control, reconnaissance, logistics, and technical support bodies (centers). All this may negatively affect the results of combat operations because of poor coordination – as happened, for example, during the deployment of a limited contingent of Soviet troops in Afghanistan (1979) and at the initial stage of the counterterrorism operation in the North Caucasus (1994). In today’s conditions, it is simply not permissible to allow such situations to be repeated.

The conclusions from projections of the possible development of the military and political situation in the world and in the country for the next five to 10 years should become the basis for changing the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations, taking into account the probability of a large-scale or regional war in any strategic area with a strong, well-equipped adversary that uses effective high-tech military assets.

Under modern conditions, the main efforts in defining the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations should be directed at ensuring the repulsion of sudden enemy aggression in the form of an aerospace operation aiming to break down the state and military administration system, and the country’s air, missile and space defenses; destroy economic facilities; and disrupt logistics and transportation activities. Also, efforts should be directed at successfully performing sudden combat missions under severe time constraints.

First of all, it is necessary to increase the combat capabilities of tactical-level combined-arms formations and their WMSE; improve the balance of the organizational and staff structure and the professional training of personnel; and improve command, intelligence, electronic warfare, and comprehensive support systems to achieve an advantage in combat potential over the probable enemy by at least 50%.

A balanced organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations makes it possible to achieve a rational ratio of quantitative and qualitative characteristics of combat and support components to realize the potential combat capabilities of all units under any conditions. It should be noted that currently this requirement is not fully observed with regard to the optimal ratio of combat and logistical units of tactical-level combined-arms formations.

The versatility of the organizational and staff structure is an important requirement implying the formation of modular combat subunits capable of successfully fighting in wars and armed conflicts of any scale and intensity. To that end, it is expedient to include modular type (light, medium, and heavy) military formations in combined-arms units and formations, taking into account their intended purpose and missions. Motorized rifle (tank) battalions should also have a modular structure.

The versatility requirement with regard to the combat systems and assets available in tactical-level combined-arms formations is met provided that their list is represented by a complete set of WMSE required for combat tasks in all main types of combat and capable of functioning without interruption under any conditions.

At the same time, the versatility requirements for strike echelon forces are somewhat higher than those for comprehensive support systems in terms of firepower, striking power, protection, and mobility. Combat vehicles, in addition, must have higher interoperability capabilities.

Systemic Requirements

Unification, meaning bringing to uniformity,9 must cover at least 70% of WMSE assemblies and units of tactical-level combined-arms formations, alongside control algorithms, software products of the information environment, etc. This requirement is quite controversial, since it is very difficult to achieve complete unification in various parts of the operational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations, whereas partial unification can provide some benefit, especially in combat training. Nevertheless, unification contributes to the stability of the operational and staff structure because it eliminates the need for radical changes in connection with the modernization or adoption of new types of WMSE when equipping tactical-level combined-arms formations.

Standardization, in a general sense, is setting rules and specifications for voluntary repeated use, aimed at achieving order in the production and circulation of products and improving the competitiveness of goods, work, or services.10 Its purpose is to achieve an optimal degree of order in a particular area through extensive and repeated use of established regulations, requirements, and norms to solve existing, planned, or potential problems. When applied to the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations, standardization should cover a maximum number of components and procedures, but at the same time, not limit the reasonable initiative and creativity of commanders (chiefs) when making combat decisions or controlling subordinate units and divisions.11

Adaptability of the organizational and staff structure means the ability of tactical-level combined-arms formations to adapt to performing combat operations in any strategic (operational) area and in various physical and geographical conditions (on flat, mountainous, forest-marshy, desert, and urbanized terrain in winter or summer) and to successfully perform their missions, destroying, as a rule, a superior enemy in an environment of the massive use of air attack weapons, precision weapons, electronic warfare, and military robotechnical systems, and in information confrontation conditions.

Protection implies reducing personnel and WMSE losses of tactical-level combined-arms formations as much as possible and ensuring the full realization of their combat potential even under the attack of the adversary’s various weapons. The importance of force protection has been increasing significantly in recent years due to the high probability of the adversary also using weapons based on new physical principles (nontraditional weapons) in combined-arms combat along with conventional weapons (including precision weapons), military robotechnical systems, nonlethal capabilities, and, in crisis situations, WMD.

All this necessitates a search for new, more effective ways to protect personnel and WMSE, as well as the inclusion into tactical-level combined-arms formations of regular forces and assets capable of successfully taking protective measures in general types of combat without involving specially trained personnel or special-purpose equipment.

Common information environment integration is ensured by the introduction of modern information exchange technologies into radio relay, wired, and satellite communication assets (including those installed on UAV or airships) and space components coupled with unified information and technical systems of adapted architecture at the communication nodes of command posts and alternate, temporary, and auxiliary control points.

It is also necessary to provide for the deployment of an information support system for the use of ground-based and airborne precision weapons and to complete the formation of the common information environment that ensures the functioning of the military control bodies of the strategic, operational-tactical, and tactical levels and interspecific weapon systems.

At the present stage, in order to fully integrate tactical-level combined-arms formations into a common information environment, it is necessary to equip them with new generation WMSE and modern equipment for military personnel, which should include information technology systems, fifth or sixth generation radio stations, sensors, actuators, switching devices, routers, batteries, electric generators, electronic computing equipment, and other necessary accessories.

Functional Requirements

In relation to the main types of combat, this type of requirement for the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations is mainly expressed in terms of impact (characteristics of volume, depth, and timing of the combat mission), firepower (capability), mobility, and self-sufficiency. When defining these requirements, the provisions of current guidance documents on the preparation and conduct of combined-arms combat and forecasts for their development for a period of three to five or more years should be taken in account.

According to the combat manual, when attacking, tactical-level combined-arms formations can strike an enemy in the main or other areas in the first echelon of a large unit, constitute its second echelon, or operate in the combined-arms (mobile) reserve. Combat goals are usually achieved by accomplishing the following tactical objectives:

● participating in seizing fire superiority, disrupting the adversary’s troop and weapon control, and repelling enemy air attacks

● advancing and deploying into battle formation

● defeating (destroying) the enemy in the assigned area of responsibility (corridor)

● repulsing counterattacks and developing the offensive in depth, pursuing the retreating enemy

● capturing important positions (objectives).

Depending on the situation and mission, tactical-level combined-arms formations can attack a defending adversary on well-prepared or hastily occupied lines (positions), as well as on a retreating or advancing one. In the latter case, it can be defeated in counterattack.

On the basis of normative guidelines, the separate motorized rifle brigade acts in the first echelon of a large unit with an assigned area of responsibility and a designated combat mission and area for continuing the offensive. In some cases – the offensive corridor, immediate (and subsequent) missions, and the area for continuing the offensive are also determined.

The second echelon brigade has a specified route of advance, lines and time of engagement, an immediate mission, and an area for further attack.

The main requirements for the separate motorized rifle brigade on an offensive mission are the defeat of an opposing enemy that has a force of one to three reinforced motorized rifle battalions, the repulsion of a counterattack by enemy reserves in cooperation with neighbors, the seizure of enemy second echelon positions, or the capture of another important position or facility.

In defense, the separate motorized rifle brigade must be able to successfully repel an attack by a group of one-and-a-half to two motorized infantry (tank) brigades, hold its position until the senior commander responds adequately, and regain the initiative. If the battle is unsuccessful and the enemy builds up its efforts, the separate motorized rifle brigade is required to maintain combat effectiveness, execute a swift maneuver out of the battle, and withdraw to a new holding line in depth where it can continue conducting defensive operations.

The firepower of a separate motorized rifle brigade assumes the ability to engage at least 15 to 20 critical enemy targets during the immediate mission and suppress about 120 to 170 other targets. In addition, it is required to systematically provide fire support to individual units operating separately from the main forces as part of forward, raiding, enveloping, special detachments, and tactical airborne assaults.

Mobility is the troops’ (forces’, facilities’) ability to move (relocate) quickly, maneuver, deploy in precombat and combat formation, and conduct combat actions (operations) at high tempo under various conditions.12 As applied to tactical-level combined-arms formations, this requirement should ensure that they can march independently up to 200 to 250 km a day at a speed of at least 25 km/h to 30 km/h, as well as be able to be transported by rail, sea, and partly by air.

Self-sufficiency implies that a separate motorized rifle brigade is able to operate in a separate area, away from the main forces of a larger unit, for three to five days. This requires carrying a minimum of four or five rounds of ammunition, three- or fourfold fuel and lubricants reserves, and necessary food supplies.

Success in combined-arms combat is largely achieved through sustained and uninterrupted command and control of troops, which ensures preemptive strikes against the enemy, effective fire defeat, impactful information warfare, and reliable force protection from enemy air strikes and artillery fire.

Therefore, the main requirement for command and control is for the information-gathering and decision-making cycle to be 50% to 100% faster than that of the adversary. This is achievable when data collection takes no more than 30 minutes, decisions are made within two hours, missions for battalions are assigned in 10 minutes or less, reports are prepared in about 10 minutes, and field command posts are deployed in 20 minutes.

The composition of command-and-control and communications units and their equipment should be determined in a way that ensures the functioning of command and control posts on the ground and on the move, near-real-time information exchange under conditions of enemy use of ECM, timely change of the deployment areas of the basic communication nodes depending on the situation, their independent protection and defense, the repulsion of viral attacks, the repair of individual nodes of automated control systems, and the availability of several redundant modules. Visually, command and control post equipment (command and staff vehicles) should not differ significantly from the combat vehicles of tactical-level combined-arms formations.

In modern conditions, an important role in accepting a battle plan and making a decision on the use of tactical-level combined-arms formations is the simulation of combat operations and calculations of the forces and assets (combat potentials) ratio to a possible enemy’s in various strategic (operational) areas. The same applies to decisions on other tactical missions, which allows for a fairly reliable determination of the success or futility of performing upcoming missions as intended. In this connection, when developing the organizational and staff structure of the command and control bodies of tactical-level combined-arms formations, as well as the latest equipment for command posts and prospective models of WMSE, it is necessary to provide for the wider introduction of calculation and modelling (calculation and simulation) systems and improve the software products for them.

Since tactical-level combined-arms formations, along with motorized rifle and tank units, include military formations of other branches or special forces, it is advisable to address the main functional requirements for their organizational and staff structure as well.

Reconnaissance units of tactical-level combined-arms formations should have an organizational and staff structure that permits the rapid and continuous collection and comprehensive analysis and vetting of information and its timely, rapid delivery to end users. Reconnaissance forces and assets must be extensively integrated into reconnaissance and strike (fire) systems to ensure the destruction of enemy targets in real time. Reconnaissance battalions of large units should be equipped with military robotechnical systems, UAV systems, including strike drones, as well as information-signaling devices (sensors) and various effective technical reconnaissance equipment.

The structure and equipment of electronic warfare units should be developed in a way that ensures the transition from frequency-division multiplexing of jamming transmitter channels to time-division multiplexing, which will allow the suppression of up to 24 enemy radio communication lines simultaneously. Their ability to conduct virus attacks and impact munitions with passive homing heads targeting air defense and field artillery should also be increased.

At the same time, it is important to develop technologies, techniques, and measures that allow EW units to quickly penetrate short-wave and ultrashort-wave ground and air communication lines; ground terminals of satellite communication; Navstar radio navigation system; EPLRS and JTIDS systems; air defense radars and field artillery; and cellular, trunk communications of the adversary; and to reliably suppress them with precision and blocking fire.

The main requirements for the organizational and staff structure of missile troops and artillery units of combined-arms formationsare the optimal combination of artillery reconnaissance assets, the reduction of the time spent on assigning missions and maneuvering, the increase of the scale and efficiency of the use of high-precision guided and programmable munitions, as well as the use of special shells – i.e., illuminating, smoke, incendiary, thermobaric, nonlethal, leaflet, ECM, and others.

The capabilities of missile troops and artillery units should also be improved to hit enemy targets in the “multiple fire attack” or “train” mode and to quickly destroy (suppress) maneuverable targets in dispersed combat order at ranges of up to 80 km using multiple-launch rocket systems and remote mining assets.

The structure and equipment of air defense (antiaircraft) units should provide effective direct protection of the combat ranks of tactical-level combined-arms formations from enemy air attacks (tactical aircraft, army aviation, cruise missiles, drones) operating at extremely low and low altitudes in various types of combat at any time of day. At the same time, the large unit’s air defense system should have high noise immunity due to integrated use of means of detection, tracking of air targets, as well as guidance of antiaircraft guided missiles and kinetic directional weapons.

A priority for improving the operational and staff structure of radiation, chemical, and biological force units should be to increase their ability to promptly reveal the enemy’s preparations for using WMD (by equipping them with sets of new and modernized NBC reconnaissance devices), to provide timely and high-quality special treatment of personnel and WMSE, to set up aerosol screens, and to use flamethrower systems that allow for the reliable destruction of the enemy in field fortifications and buildings. In the perspective under consideration, the use of airborne NBC reconnaissance systems should also be expanded.

In developing the organizational and staff structure of engineering support units, special attention should be paid to enhancing their tactical mobility and capabilities to reliably protect tactical-level combined-arms formations in any environment. It is also extremely important to increase the effectiveness of engineer ammunition by programming their use, reducing the assortment, creating reconnaissance and defensive systems for hitting group targets, and deploying and implementing a universal minelaying system that makes it possible to install minefields with coordinate fixing. It is expedient to continue modernizing multifunctional engineering vehicles, sets of linear metal structures for building portable bridges, as well as bridge launchers, assault-crossing ferries, ferry-bridge vehicles, pontoon parks, and other engineering armaments.

The structure of units equipped with military robotechnical systems should be determined so as to ensure high effectiveness when conducting military, engineering, and RCB reconnaissance; guarding locations (concentrations) of troops; waging counterbattery warfare; destroying enemy objects; creating engineering obstacles; clearing passages in mixed minefields; laying communications cables; disposing of casualties and recovering shot-up vehicles; and delivering fuel, lubricants, ammunition, and other materiel13 (see Fig. 2).14,15

|  | |

| Uran-9 | Uran-14 | |

|  | |

| Udar | Soratnik |

Fig. 2. Russian military robotechnical systems

Improvement of the organizational and staff structure of UAV systems-equipped units should focus on enhancing their capabilities to reconnoiter terrain and the enemy issue precise coordinates of objectives (targets); set up electronic jamming; and deliver precision strikes on command posts, artillery positions, army aviation units, and air defense facilities, including through the use of loitering munitions.16

The main requirements for the organizational and staff structure of units equipped with weapons based on new physical principles is to ensure their ability to create certain impact zones with laser, ultrahigh frequency, and other directed-energy weapons to increase the effectiveness of conventional weapons. The weapons based on new physical principles can be integrated both by installing relevant equipment on regular WMSE or by creating platoon or battery units that are reasonable for use in combat, depending on the emerging situation, independently or in conjunction with conventional engagement assets.

The constant readiness of troop (forces) groupings to act as intended is most often ensured by the high-quality and intensive combat training of tactical-level combined-arms formations; the introduction of new approaches to its organization; and the allocation of sufficient ammunition, fuel, lubricants, and other materiel for this purpose. The main emphasis in improving combat training should be on formations that are to be used as part of interagency troops (forces) groupings.

The capabilities of tactical-level combined-arms formations and the rationality of their organizational and staff structure should be assessed during random checks of their readiness to perform their tasks as intended, as well as during multistage and bilateral tactical and command-and-staff exercises. In our opinion, the main indicator of the combat readiness of the Ground Forces is their ability to respond quickly and adequately to any military threat; this concerns peacetime combat personnel especially.

In modern conditions, the need to develop the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations in accordance with the requirements presented in this article and to determine a reasonable ratio and integration in their composition of units and subunits of various branches of troops and special forces is conditioned by the continuous threat of armed conflicts of various intensity and their subsequent escalation into local, regional, or large-scale warfare using both conventional and nuclear weapons, as well as by the urgency of finding and introducing new forms and ways of conducting military (combat) operations.

It is advisable to assess the combat capabilities of tactical-level combined-arms formations based on a functional approach to their organizational and staff structure as a complex combat system operating in a particular tactical environment.

The above analysis of factors, principles, and trends influencing the requirements for the combat capabilities of tactical-level combined-arms formations makes it possible to formulate the following priorities for the development of their organizational and staff structure:

● improving the control system and creating a unified information environment, thus ensuring the coordinated effective actions of forces and equipment involved in the battle within unified spatial and temporal parameters on a real-time basis

● developing and implementing a modular structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations, thus allowing for the formation of groupings of forces and equipment for actions in accordance with the prevailing situation without changing the organizational and staff structure

● organizing tactical-level combined-arms formations for conducting combat operations in special physical and geographical conditions (in mountainous, forested, or desert terrain or in northern areas) and for performing special missions as part of raiding teams, enveloping groups, assault detachments, tactical airborne assault landings, etc.

● creating a weapon system for tactical-level combined-arms formations and stepping up the pace of their reequipment with modernized and prospective WMSE

● developing the organizational and staff structure of units and subunits of other branches and special forces that are part of tactical-level combined-arms formations.

We believe that implementing the above areas for optimizing the organizational and staff structure of tactical-level combined-arms formations will make it possible to seek and introduce new and more effective forms and ways of conducting combat actions (operations), enabling missions to be successfully accomplished as intended in armed confrontation with equivalent formations of a strong potential adversary in the near and more distant future.

NOTES:

1. Voyennoye iskusstvo v lokal’nykh voynakh i vooruzhonnykh konfliktakh [Military Art in Local Wars and Armed Conflicts]. Voyenizdat Publishers, Moscow, 2008, 764 pp.

2. Voyennaya doktrina Rossiyskoy Federatsiyi. 25 dekabrya 2014 goda [Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation. December 25, 2014]. URL: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/420246589 (Retrieved on January 12, 2022.)

3. Sukhoputniye voyska [Ground Forces]. Portal Ministerstva oborony RF [Portal of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation]. URL: https://structure.mil.ru/structure/forces/ground/task.htm (Retrieved on January 12, 2022.)

4. Ibid.

5. Voyennaya doktrina Rossiyskoy Federatsiyi [Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation].

6. A.V. Vdovin, Adaptivniy podkhod k primeneniyu sil i sredstv dlya bor’by s terroristami po opytu vooruzhonnykh konfliktov za predelami Rossiyi [An Adaptive Approach to the Use of Forces and Assets to Combat Terrorists Based on the Experience of Armed Conflicts Outside of Russia]. Voyennaya Mysl’, # 5, 2018, pp. 30-36.

7. Federal’niy zakon ot 31 maya 1996 g. № 61-FZ “Ob oborone” (s izmeneniyami i dopolneniyami) [Federal Law of May 31, 1996 No. 61-FZ On Defense (with amendments and additions)]. URL: https://base.garant. ru/135907/94f5bf092e8d98af576ee351987de4f0/ (Retrieved on January 11, 2022.)

8. A.V. Khomutov, Countering the Multi-Domain Operations of the Adversary. Military Thought, Vol. 30, No. 3 (2021), pp. 49-67.

9. S.I. Ozhegov, Slovar’ russkogo yazyka [Dictionary of the Russian language]. ONIKS 21 vek Publishers, Moscow, 2003, p. 816.

10. Rosstandart [Federal Agency on Technical Regulating and Metrology]. URL: https://www.gost.ru/portal/gost/home/activity/standardization (Retrieved on January 12, 2022.)

11. V.V. Trushin, O tvorcheskom podkhode k upravleniyu voyskami [On a Creative Approach to Command and Control]. Voyennaya Mysl’, # 8, 2020, pp. 6-18.

12. Voyenniy entsiklopedicheskiy slovar’ [Military Encyclopedic Dictionary]. Portal Ministerstva oborony RF [Portal of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation]. URL: https://encyclopedia. mil.ru/encyclopedia/dictionary/details.htm?id=8208@morfDictionary (Retrieved on January 03, 2022.)

13. A. Tikhonov, D. Gorskiy, Boyeviye roboty rasshiryayut vozmozhnosti [Combat Robots Expand Opportunities]. Krasnaya zvezda. February 4, 2022.

14. K. Ryabov, Boyeviye i Inzhenerniye Robototekhnicheskiye kompleksy dlya Rossiyskoy armiyi [Combat and Engineering Robotechnical Systems for the Russian Army]. Voyennoye obozreniye. August 20, 2021. URL: https://topwar.ru/186153-boevye-i-inzhenernye-robototehnicheskie- kompleksy-dlja-rossijskoj-armii.html (Retrieved on February 05, 2022.)

15. А. Boyko, Katalog voyennykh nazemnykh robotov razlichnogo naznacheniya [Catalog of Military Ground Robots for Various Purposes]. RoboTrends. URL: robotrends.ru/robopedia/katalog-nazemnyh-voennyh-robotov- razlichnogo-naznacheniya (Retrieved on February 05, 2022.)

16. A.I. Kalistratov, Kamikadze XXI veka [Kamikaze of the 21st Century]. Armeyskiy sbornik, # 4, 2021, pp. 65-75.