Some of the Zhengzhou Museum collections of inscribed bronzes were not published, including three gu-goblets, one jue-cup, one li-cauldron and one spear head. Below is a summary discussion of these six artifacts.

1. One gu-goblet ![]() (Artifact ZH1496), submitted by the former Henan Cultural Heritage Task Force (now the Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology) in 1958. The artifact height is 25.2 centimeters, opening diameter 15.1 cm and bottom diameter 9 cm. The goblet is skinny and tall, and consists of three sections. It has a large opening, expanding upper belly, narrow waist, and trumpet-like high ring foot. Its upper belly is decorated with four sets of a banana leaf pattern; the waist has two sets of an inward curled animal mask pattern and a ring foot with four sets of a curling dragon pattern. All the decorated patterns are over a thunder pattern background. The junction area of the ring foot and the waist contains two lines of convex line pattern, with four cross-shaped holes between the lines. An inscription “

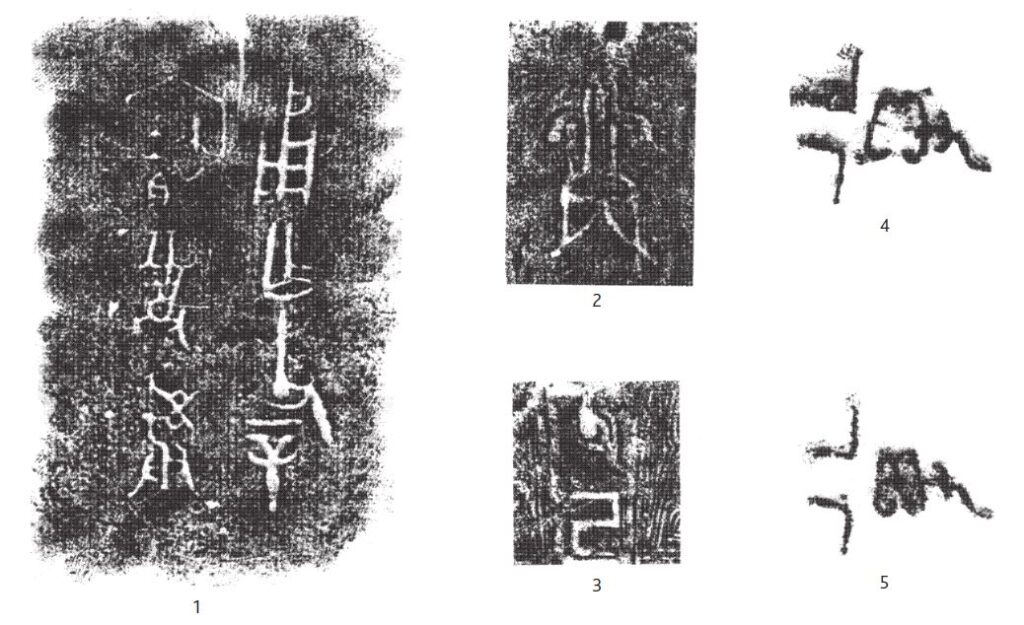

(Artifact ZH1496), submitted by the former Henan Cultural Heritage Task Force (now the Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology) in 1958. The artifact height is 25.2 centimeters, opening diameter 15.1 cm and bottom diameter 9 cm. The goblet is skinny and tall, and consists of three sections. It has a large opening, expanding upper belly, narrow waist, and trumpet-like high ring foot. Its upper belly is decorated with four sets of a banana leaf pattern; the waist has two sets of an inward curled animal mask pattern and a ring foot with four sets of a curling dragon pattern. All the decorated patterns are over a thunder pattern background. The junction area of the ring foot and the waist contains two lines of convex line pattern, with four cross-shaped holes between the lines. An inscription “![]() ” is cast in the inner wall of the ring foot. This character is probably a clan emblem of the maker of this artifact. The date of this goblet is the late Shang Dynasty (Figure 1 and Figure 8:2). The character

” is cast in the inner wall of the ring foot. This character is probably a clan emblem of the maker of this artifact. The date of this goblet is the late Shang Dynasty (Figure 1 and Figure 8:2). The character ![]() as a place name appeared in one of the Yin Ruins inscriptions. (Collections 20398): “Divined on Ding Wei: order [person] Zheng

as a place name appeared in one of the Yin Ruins inscriptions. (Collections 20398): “Divined on Ding Wei: order [person] Zheng ![]() to conquer [place names]

to conquer [place names] ![]()

![]() and Bo.”[1] The place names

and Bo.”[1] The place names ![]() and Bo were on the same divine oracle, so it can be speculated that

and Bo were on the same divine oracle, so it can be speculated that ![]() may be close to Bo.

may be close to Bo.

2. Two “得” (De) gu-goblets, submitted by the former Henan Cultural Heritage Task Force in 1958. They were collected at Jianxi Reservoir in Meng County, Henan Province in October 1956. [2] The height of Artifact ZH1477 is 22 cm, opening 14 cm, bottom diameter 8 cm and weight 0.69 kilograms. It is severely corroded. The height of Artifact ZH1495 is 21.4 cm, opening 14 cm, bottom diameter 8 cm and weight 0.7 kg. The shapes and decoration of these two goblets are identical. Both have expanding opening, square lips, long necks, slightly puffed mid-bellies and ring feet extended outward. Their bellies are decorated with thunder patterns in inattentive lines. The overall bodies are decorated with an inward curling animal mask pattern with eyes slightly raised. Inside the inner wall of each goblet, a casting inscription “![]() ” is found, and both are raised inscriptions (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figures 8:4 and 8:5).

” is found, and both are raised inscriptions (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figures 8:4 and 8:5).

The character ![]() has a left prefix 彳 as a hand holding a shellfish, and is deciphered as the character 得. In Phase I of the divine inscriptions of Yin Ruins, the character 得 is a name for a person or a clan, such as:

has a left prefix 彳 as a hand holding a shellfish, and is deciphered as the character 得. In Phase I of the divine inscriptions of Yin Ruins, the character 得 is a name for a person or a clan, such as:

- “Divine whether indeed to order 得” (Collections 4719);

- “Divined on [two illegible Chinese characters]: Zheng [divined] whether to order 得 …… to farm …… in the 12th moon” (Collections 9495);

- “Divine whether to instruct 得 on farming” (second divination on the same subject, Collections 9496);

- “Divine whether Shu should order 得” (Collections 28094).

In bronze inscriptions, the Chinese character 得 was used as the name of a person or clan. There is a bronze yan-crock of the father of the 得 family (Compilations 0844)[3]; “得” ding-tripod (Compilations 1066, 1067 and 1476); “亞得” Father Geng ding-tripod (Compilations 1880); “得” you-wine container (Compilations 4795); “亞得” Father Kui you-wine container (Compilations 5094); “亞得” He dan-goblet (Compilations 6505); “得” gu-goblet (Compilations 6634 and 6635); “得” Father Yi gu-goblet (Compilations 7086); “得” jue-wine cup (Compilations 7439); “亞得” Father Ding he-pitcher (Compilations 9375); “得” lei-jar (Compilations 9742);“得” Father Kui square ding-tripod (Diaspora 51)[4]; etc. All of the above bronze vessels belong to the late Shang Dynasty. From the shape and inscriptions of the two “得” gu-goblets discussed in this article, they also belong to the era of the late Shang Dynasty.

3. One piece of a Father Yi jue-wine cup (Artifact ZH1478), collected by the Zhengzhou Museum in 1963. The height of the artifact is 17.5 cm, cup depth 8.5 cm and weight 0.85 kg. The spout is very wide and thick, the tail tip is pointing up, and the cup is deep and has a round bottom with three outward feet. Two mushroom-shaped pillars are at each side near the root of the spout on the rim. It is a decorated with curling pattern. A bull-head handle attaches on one side of the neck and belly. The jue-wine cup belly is decorated with a polygonal animal mask pattern, filled with cloud and thunder patterns. A cast inscription of Chinese characters “父己 [Father Yi]” is engraved inside the handle. The caps of these pillars are very tall, in the style of transitioning toward the handle. The date of the artifact is the end of the Shang Dynasty and the Early Zhou Dynasty (Figure 4 and Figure 8:3).

4. One piece of a Father Xin li-cauldron (Artifact ZH3967) was collected at Xiaogou [lit. “Small Ditch”] Village in Gongyi County in March 1984.[5] Its height is 22.5 cm, diameter 18.8 cm and weight 1.7 kg. It has an expanding opening, blunt lip and slightly narrow neck, with a pair of symmetrical square, erect ears decorated with a pottery pattern. Its belly is slightly puffed, with a separated crotch and low column feet. Ears and feet are positioned in a pentagonal distribution. Plan view of the opening shows a slightly round cornered triangle shape. The neck is decorated with cloud pattern and mostly corroded. Traces of soot can be seen under the crotch and around the feet. Seven cast inscription characters “甬作父辛宝尊彝 [Yong casts (deceased) Father Xin a precious and prestigious vessel]” are found on the inner wall near the opening. Of these, 甬 (Yong) might be the name of a person. This cauldron very closely resembles the Mai li-cauldron (Artifact IIM251:16) found in the Liuli River in Beijing, which is dated between Kings Cheng and Kang of the Western Zhou Dynasty. Therefore, this artifact’s date is probably no earlier than the early Zhou Dynasty (Figure 5 and Figure 8:1).

5. One piece of a “Jing Zou Ku [left-side weaponry casting workshop]” mao-spear head (Artifact ZH4885) was unearthed in the south courtyard of the office complex of the Chinese Communist Party Committee of Henan Province in February 1966. Its remaining length is 11.2 cm and width 2.8 cm. The body of the mao-spear head is in a willow leaf shape, with a diamond-shaped cross section, sharp ridges, and part of the stem missing. A line of three characters “京左库” (Jing Zou Ku) is inscribed on the left side of the ridge on the mao-spear head. The strokes of these characters are clearly engraved. The word Zou Ku is common in weapons used in three marches [i.e., states] of the later Jin March during the Warring States Period. According to data of the inscriptions on the cached weapons found in Baimiao Village, Xinzheng City, the weaponry casting of the Han March during the Warring States Period often contains inscriptions of words such as “Wu Ku [weaponry casting workshop]”; “Zou Ku [left-side weaponry casting workshop]”; “You Ku [right-side weaponry casting workshop]”; “Zhi Ku [weaponry casting workshop of Zhi]”; etc.[7] Judging from the shape and inscriptions, this mao-spear head is a weapon of the Han March from the late Warring States Period (Figures 6 and 7).

The character 京 (Jing) in the inscriptions is the name of a place. Weapons with the inscription “京” are also found on a Jing ge-dagger-ax (Compilations 10808); a dagger-ax ordered in the ninth year of [the reign of] Jing[8]; etc. In addition, the characters 京昃 (Jing Ze) are found in pottery inscriptions unearthed in the Zhengzhou and Xingyang areas (Collections of Pottery Inscriptions 6.48)[9] and on a Jing hu-measuring container (Collections of Pottery Inscriptions 6.51). There are quite a few flat shoulder hollow head knife coins with cast inscriptions of the character 京, as included in Currency Systems 386, 388, 389 and 391.[10] Therefore, 京 is a place that not only casts weapons, but also mints coins. The site of a town called 京 is located about 10 km southeast of today’s Xingyang City near Jingxiang Village at the border junctions of Yulong Town, Jiayu Town and Qiaolou Town. The city wall remaining today on the ground surface is more than 2,800 meters long and rises more than 10 m above the ground surface.[11] There are rich records related to this town in various historical records, such as Book of Gongyang and Book of Guliang, [both of] which state: “Autumn, 7th moon, Ji Wei, allies gathered in the north of Jing Town.”[12] Grand Historical Records: Biography of Yu Xiang: “Chu … and Han battled between the towns of Jing and Suo, south of Yingyang City.” The Meaning of Historical Records, as cited in the Journal of Geography, says: “The county seat of Jing is located twenty li (10 km) south of Yingyang County of Zhengzhou: [it is] Jing Town, located in Zheng Duchy.”[13] According to the Zuo Zhuan [Commentary of Zuo on the Spring and Autumn Annals]: “In the first year of the reign of Duke Yin, the early Spring and Autumn Period, Wu Jiang asked Jing Town for Gong Shu, let him stay there and called him Uncle Jing Town.” Yu Du noted: “Jing, a Town of Zheng.” Today’s Jing County is located within Yingyang city.[14] Jing Town belonged to Zheng during the Spring and Autumn Period, and belonged to Han during the Warring States Period; it was under the jurisdiction of Sanchuan Prefecture during the Qin Dynasty. It belonged to Henan Prefecture during the Han Dynasty, when Jing County was established.

__________________________________

Acknowledgments

Photography: Wei Chen

Rubbings: Lan Zha

__________________________________

References Cited

[1] Guo, Mourou, 1978-1982 Oracle Collections (referred to in the article as “Collections”). Zhonghua Book Company.

[2] Cultural Relics Task Force of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs of Henan Province. 1961 The excavation at Jianxi Site in Meng County, Henan Province, Archaeology No. 1. However, the summary report of the excavation did not mention these two goblets.

[3] Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Science. 2007 Compilations of Bronze Inscriptions of the Yin and Zhou Dynasties (referred to in the article as “Compilations”). Zhonghua Book Company.

[4] Liu, Yu and Tao Wang. 2007 Catalog of Bronze Vessels with Inscriptions from the Yin and Zhou Dynasties Diaspora in Europe and America (referred to in the article as “Diaspora”). Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House.

[5] Chen, Lixin. 1986 The early Western Zhou Dynasty Bronze Ge found in Gong County. Cultural Relics of Central Plains No. 4.

[6] Beijing Institute of Cultural Relics. 1995 The Cemetery of the Yan State of the Western Zhou Dynasty in Liuli River (1973-1977), pp. 140, 161. Cultural Relics Press.

[7] Hao, Benxing. 1972 Discovery of a Cache of Bronze Weapons of the Warring States Period in the “Old Towns of Zheng and Han” in Xinzheng City. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) No. 10.

[and]

Kou, Yuhai. 1992 Discovery of an Engraved Bronze Spear Head in Xinzheng City. Cultural Relics of Central Plains No. 3.

[8] Fang, Hui. 1998 Studies of a “Ninth Year Jing Order Dagger-Ax.” China Cultural Relics News Sept. 23.

[9] Gao, Ming. 1990 Compilations of Ancient Pottery Inscriptions (referred to in the article as “Pottery Inscriptions”). Zhonghua Book Company.

[10] Wang, Qingzheng. 1988 The Pre-Qin Dynasty Currencies: Complete Catalog of Ancient Chinese Currency Systems (referred to in the article as “Currency Systems”). Shanghai People’s Publishing House.

[11] Cultural Heritage Record Compilation Committee of Yingyang. 2011 Cultural Heritage Record Compilations, p. 62. Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House.

[12] Ruan, Yuan (Qing Dynasty). 1980 Commentary to the Thirteen Classics, pp. 2304, 2427. Zhonghua Book Company.

[13] Sima, Qian (Han Dynasty). 1963 Grand Historical Records: Biography of Yu Xiang, p. 324. Zhonghua Book Company.

[14] Same as [12], p. 1716. Wenwu (Cultural Relics) Editors: Tong Zheng and Yanming Zhou

Translated by Garry Guan

This article was originally published in Wenwu (Cultural Relics) No. 11, 2013, pp. 73-75, 77.