Abstract. This article attempts to summarize and categorize Tatyana Zaslavskaya’s contribution to the study of post-communist transformation processes. The focus of attention is the “social mechanism of the transformation process,” its main features and cognitive capacity, and the basic building blocks and relationships of the original “activities-structural” conception of this mechanism. It is shown that Zaslavskaya’s conception, when used to explain the patterns and regularities of real social change, provides future researchers with effective and relevant theoretical and methodological tools for further exploratory research.

Tatyana Zaslavskaya needs no special introduction. Her name is well known to all generations of economists and sociologists, both the oldest and the youngest, in Russia and abroad. She was one of the leading social scientists in Russia, a prominent specialist in the field of sociology and economics, and the founder of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology, which has had a significant effect on the development of Russian sociology.

Zaslavskaya always focused on very complex and pressing problems of the economy and society that required a systemic approach. From the study of the economic problems of distribution according to work on collective farms in the 1950s and migration of the rural population in the 1960s, she turned to a systemic study of socioeconomic life in some territorial units, structures and sectors (rural settlements, districts, regions, agrarian sector) in the 1970s. later on, she studied the social mechanism of the functioning and development of the economy (in the 1980s) and the social mechanism of the transformation of society as a whole (in the 1990s and 2000s). the purpose of this article is to try to understand and, if possible, systematize Zaslavskaya’s contribution to the study of post-communist transformation processes, which is closely associated with her conception of social mechanisms.

This conception of Zaslavskaya arose and developed in response to the challenges of practice and the need to create methodological tools for an effective and timely empirical analysis of painful problems facing the economy and society. Viewing the development of the economy as a social process driven by the interests and resources of various groups, Zaslavskaya called into question, back in the early 1980s, the “sacrosanct” belief in the “indisputable advantage of socialist relations of production over capitalist ones” [24, p. 73], and with the start of perestroika she came to be known as one of its “foremen.”

In the 1990s, she went on to study the social mechanism of the transformation of society as a whole and was one of the first to correctly determine both the type and the likely prospects of the transformation process in Russia. The practical importance of her scientific conclusions for developing a strategy and enhancing the efficiency of socioeconomic transformations cannot be overestimated. But the demand for them depends on factors such as the ability of the ruling class to realize the need for transformations and on whether it has the political will to implement them. Unfortunately, it must be admitted that there is not much likelihood of the results of her research being actually put into practice. But they will retain their scientific importance; moreover, judging by the trends in the development of scientific knowledge, their importance is bound to increase.

The point is that in the last 10 to 15 years, Western social thought has seen not only a revival but also an active increase of interest in theoretical approaches based on social mechanisms (see, for example, [1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16, 19, 20]). It was stimulated by dissatisfaction with the explanatory power both of certain general laws of social development and of a purely multivariate statistical analysis of data. True, the concept of “social mechanism” is still very vague and unclear: the number of definitions compares with the number of authors and sometimes even exceeds it [12, pp. 579-580; 14, p. 239]. Different researchers “discover” different kinds of social mechanisms, and there is no agreement between them on the relationship between these mechanisms either.

Overall, the discussions around social mechanisms are dominated by questions arising in the theory of knowledge proper: how does mechanism-based (“mechanismic”) methodology relate to the principle of methodological individualism, the traditions of pragmatism, critical realism, etc.; should the definition of a social mechanism include the initial conditions and the results of its implementation; actors at what level should be taken into account, etc.? Not all of these theoretical and methodological questions were raised or considered important by Zaslavskaya. But her conception, formulated in response to the challenges of practice and tested by her and her followers in the context of different economic and social practices and different sectors of the economy and society, makes it possible to clarify many questions regarding social mechanisms being raised today in Western social thought.

On the Category of “Social Process Mechanism”

The category of “social mechanism” became central to Zaslavskaya’s research back in the late 1970s and early 1980s in reference to the functioning and development of the socialist economy. her colleagues and students used the mechanismic methodology in studying specific subsystems and processes, and eventually the category of “social mechanism of the functioning and development of the economy” (or “social mechanism of economic development,” SMRE) became the signature of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology (NESSh). Social mechanism of economic development meant “a stable system of behavior of social groups and their interactions with each other and with the state regarding the production, distribution, exchange and consumption of material goods and services; a system regulated by the social institutions of a particular society (party, state, economic mechanism, institutions of culture and ideology), on the one hand, and by the socioeconomic status and consciousness of these groups themselves, on the other” [30, pp. 23-24; 33, pp. 12-13; 42, pp.

59-61].

In the 1990s, Zaslavskaya applied her mechanismic methodology to an analysis of transforming society as a whole: at first, it was a mechanism of the socioeconomic transformation of society [35; 36, pp. 152-170], and then a social mechanism of the transformation of post-communist societies as a societal process [37, pp. 149-167; 36, pp. 184-204, 445-468; 31, pp. 3-16]. By social mechanism of the transformation process she meant a stable system of interactions between social actors of different types and at different levels (individuals, organizations and groups), which is regulated by the basic institutions of society (rules of the game), on the one hand, and by the interests and capabilities of the actors (social status, cultural peculiarities, etc.), on the other, and which helps to bring about a fundamental change in the social order [36, p. 199; 27, pp. 199, 200-201].

The idea of mechanisms of social processes is based on the assumption that the set of phenomena, factors and dependencies that determine these processes constitute a single (holistic) phenomenon (a closed loop of relationships [30, p. 24]), and that a study of its structure helps to gain a deeper understanding of the patterns and regularities being investigated [27, p. 199]. Among the main features of social mechanisms Zaslavskaya includes their ability to regulate social processes, which “is explained by the special significance, strength and stability of the social relationships that make them systemic”; their relatively high inertia associated with the coexistence within the social mechanisms of elements belonging to the past and the present, and also the simultaneous presence within these mechanisms of phenomena that develop spontaneously, in a natural historical way, and those that are created deliberately [27, pp. 199-200].

It can be assumed that theorizing based on the mechanismic approach was precisely what helped Zaslavskaya to determine, quickly and correctly, the type of the transformation process that was taking place in Russia at least from the mid-1990s. In her opinion, the essence of this process (which was variously described by researchers at that time as a revolution, a transition or a radical reform and which was explored on the basis of various development theories such as social formations, modernization, neo-modernization, etc.) is best expressed by the concept of social transformation of society. She listed the main distinguishing features of this process as follows:

- gradual and relatively peaceful nature of the process;

- orientation towards changes in the essential features that determine the societal type of society rather than in some of its specific aspects;

- fundamental dependence of the course and results of the process on the activity and behavior not only of the ruling elite, but also of mass social groups;

- poor controllability of the process, a major role of spontaneous factors in its development, and its indeterminate results;

- inevitable, long and deep state of anomie caused by the faster disintegration of old social institutions compared to the creation of new ones [36, pp. 445-446; 27, p. 197].

Since social transformation ultimately changes the societal type of society, it appears as a more complex process than targeted reform of societies implying the preservation of their typological identity. The mechanisms and drivers of social transformations are more complex and diverse than those of social transitions with known “destinations” and directed by generally recognized leaders [36, p. 190]. “Metaphorically speaking, a transition can be compared to crossing a quiet river when the desired landing place on the other side is in view and when the necessary vessel is available. As for transformation, such a process is similar to the movement of a boat in an unknown river with many whirlpools and rapids. In these conditions, the direction of the movement is virtually independent of the helmsman, while his main task is to prevent the boat from capsizing, to minimize the damage and losses, and ultimately to land on either shore” [27, p. 196].

The new horizons of scientific knowledge opened by the category of social mechanism of transformation processes are associated with the possibility to present the social transformation process, which actually determines the future of the transforming communities, as a kind of whole, where all elements are interrelated and interdependent. As a result, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of the peculiarities and prospects of the transformation process and to determine how the social actions taken by actors at the micro level change the macro characteristics of society and how the change in these characteristics, in turn, affects the life and activity of these actors. In addition, the use of this concept allows us to raise the question of different types and social quality of mechanisms regulating transformation processes in different societies [36, pp. 193, 204; 27, p. 212].

On Zaslavskaya’s Contribution to the Study of Post-Communist Transformations

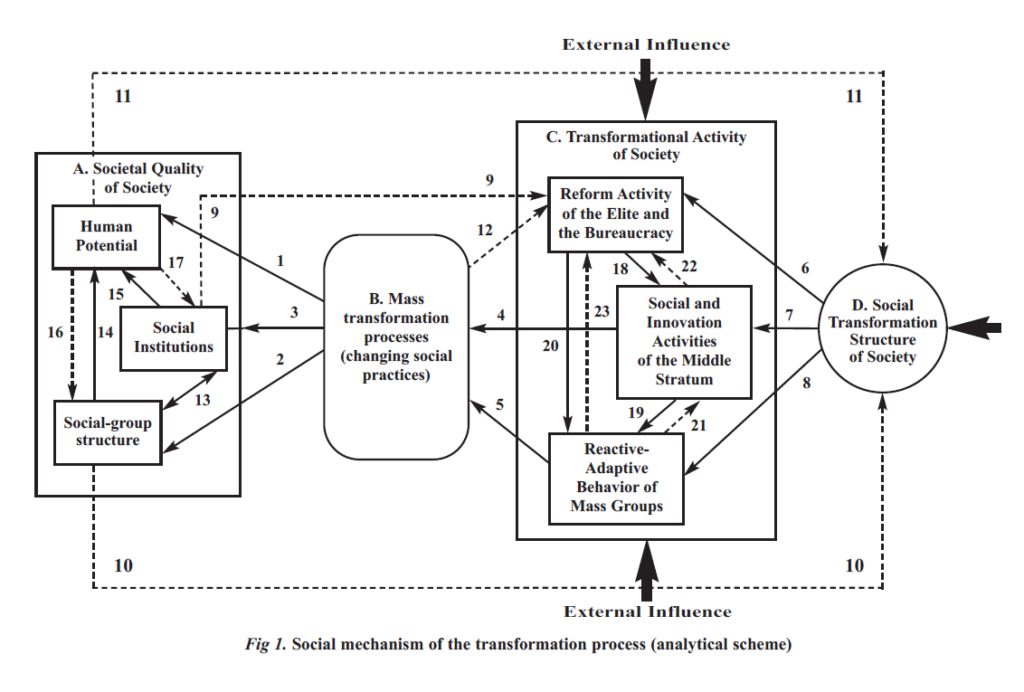

Whether the category of social mechanism will perform its prescribed role depends on the content of the broader analytical framework with which it is intertwined. Zaslavskaya developed an original activity-structural conception of the transformation process, whose main elements and relationships were presented in an analytical scheme of the social mechanism (Figure 1. Source: [27, p. 202]).

A detailed description of the main blocks and relationships can be found in a number of works (see, for example, [36, pp. 193-203; 27, pp. 200-210]). Several monographs and many articles by Zaslavskaya are devoted to their validation and study. Briefly speaking, Block A (“Societal quality of society”), which reflects the key characteristics of transforming societies as integrated systems, is called the societal (or results) block. Block B, denoted as “Mass transformation processes (changing social practices),” where the actions of actors at different levels are at the input and the macro characteristics of society are at the output and which “holds the mystery” of the transformation of individual and group social action into macro processes, is called transitional. Block C (“Transformational activity of society”), which is the “heart” of the mechanism being studied, is called the activity block, or the mechanism proper. It characterizes the interrelated types of transformational activity of social actors at different levels and of different types and shows how the social practices of society change. Finally, Block D (“Social transformation structure of society”) is called the agency block because it reflects the composition and relationships between the macro agents of transformation processes and answers the question of what cultural and political forces are ultimately “responsible” for changing the societal type of society.

The functioning of the social mechanism is ensured by feed-forward and feedback between its blocks and elements. Feed-forward links between blocks (arrows 1-8) are supplemented with feedback links (arrows 9-12), which turns the social mechanism into a relatively closed-loop system and reflects its reproductive character.

This brief enumeration of the main blocks and relationships helps to systematize Zaslavskaya’s contribution to the study of post-communist transformations. Without claiming to be exhaustive, I will list what I see as the key propositions.

- Significant enrichment of the conceptual framework and tools for studying post-communist transformations. concepts such as “social transformation,” “social mechanism of the transformation of society,” “social transformation structure of society,” “transformational activity,” “innovative-reform potential of society,” types of actors and levels of the transformation process can be regarded as basic concepts.

- Validation of the criteria for evaluating the course and results of the transformation process based on the construction of a three-dimensional space of post-communist transformations that includes the main macro characteristics of society: institutional system, social (social-group) structure and human potential, and also the relationships between them. validation of the range of institutions that play a key role in determining the societal type of a transforming society (Block A).

- Introduction into scientific use of the concept of “transformation structure of society” in order to reflect the specific societal quality of society, which is particularly important in periods of radical change, i.e. society’s capacity and readiness for self-development (Block D). Separation of the stratification and transformation structures of society in the analytical scheme. Development of methodological approaches to the study of the transformation structure based on the identification of two relatively independent but equally important projections: vertical (social-hierarchical) and horizontal (cultural-political) and their subsequent intersection. this makes it possible to build a more complex and solid model of the transformation structure, to make a more accurate assessment of the resources of macro agents (the key drivers of transformation), the level of their consolidation and social embeddedness, and consequently their role in the transformation process (see, for example, [32; 27, pp. 272-275; 34, pp. 292-312]).

- Development of the concept of “transformational activity” and a typology of transformational behavior that organically integrates changes at different levels of the transformation process (macro, meso and micro) into a single whole. An assessment of behavioral strategies simultaneously in terms of their functions in relation to actors (achievement-related, adaptive, regressive, destructive) and in terms of their consequences for society (constructive, destructive, mixed) helps to get a better idea of the social efficiency of transformation (see, for example, [27, pp. 202-239, 246-255]).

- Application of mechanismic methodology to an analysis of specific (compared to society as a whole) transformation processes; illustration of the effectiveness of its concretization with a case study of one of the most “painful” transformation processes characteristic of modern russia: the spread and institutionalization of unlawful social practices [27, pp. 256-263; 43-46; 49; 50].

- Development of theoretical, methodological and methods frameworks and large-scale empirical research exploring various elements and relationships in the analytical scheme of the transformation process. A study of members of different strata as potential and current actors in the ongoing transformation process and an assessment on that basis of the innovative-reform potential of different strata [37, pp. 149-167; 26, pp. 18-31; 36, pp. 455-464, 494-503; 27, pp. 285-306; 29, pp. 13-25]. Judging by citations in the scientific literature, these works have attracted strong interest for many years, encouraging further scientific investigation in different areas such as the social structure and stratification of Russian society [36, pp. 258-400, 453-467; 37, pp. 149-167; 42, pp. 228-257], its business stratum [36, pp. 334-358; 23] and middle strata [36, pp. 468-494; 40], the functional types of adaptive behavior [36, pp. 511-515; 22, pp. 13-19], the human potential of society [25; 34, pp. 348-387; 29], and others.

- Monitoring of the qualitative composition and activity characteristics of the new generation of business people in Russia as a potential modernization force based on an integrated study of agent-activity, social-group and institutional aspects of the transformation process [28; 38; 29; 47; 48; 41].

- Assessment of possible and probable scenarios for Russia’s development based on the activity-structural conception of the social mechanism of the transformation process taking into account the interrelation and relative autonomy of different levels of social reality and the interests and resources of actors at different levels [27, pp. 381-399; 34, pp. 292-312].

- Development of an original analytical scheme of the social transformation mechanism, which is of instrumental importance in its own right. It helps to see the “blank spots” in the study of some blocks and relationships; studies of specific blocks and relationships appear as parts of a whole, which helps to step up relevant research in a particular society, including on an interdisciplinary basis. In addition, the scheme facilitates comparative studies of transformation processes in different postcommunist societies, helping to identify the differences in the “social quality of mechanisms regulating transformation processes in different societies,” especially since the latter “differ not so much in the composition of elements and relationships (most of which are of a “cross-cutting” nature) as in their specific national ‘filling,’ content, quality and effectiveness” [36, p. 204; 27, p. 211]. As a result, not only the studies of transformation processes in a particular society, but also their international comparisons assume “a more systemic and targeted character” [27, p. 212].

- Clarification of a number of epistemological questions currently being discussed in Western sociology and philosophy of science in reference to the category of social mechanism. This clarification is based on the activity-structural conception of the transformation process, which rests on a solid empirical foundation, on a constant and close integration of theory and empirical research (theory as a tool of empirical research, and empirical research as a tool for verifying theory). Within the framework of this article, it is impossible to examine each of the above propositions in detail. I will take a closer look at three of them requiring additional explanation, at least as i have formulated them above.

Evaluation of the Course and Results of the Transformation Process: Validation of Criteria

There is still no agreement in the research community about the criteria for assessing the course and results of post-communist transformations. Some highlight various institutional changes (economic, political, legal), others focus on changes in the system of social inequalities, and still others, in the level and quality of the human potential of society, including changes in value orientations and behavior models. The lack of systems research in this area is manifested in a wide range of assessments and their easy infiltration by political and ideological “corrections” and manipulations. For example, those who emphasize institutional changes and ignore adverse trends in the social-group structure and the quality of the human potential more often speak of the successes of reforms, while negative assessments more often come from those who focus attention on social criteria but do not take into account the emergence of new social institutions and social practices [27, pp. 107-108].

In Zaslavskaya’s conception, the space of post-communist transformations simultaneously includes three key macro characteristics of societies: institutional system, social (social-group) structure and human potential, and also the relationships between them (Block A). Hence, the systemic result of transformations at any point in time is based on an integrated analysis of the dynamics of three aggregate indicators: the effectiveness of institutional systems, the quality of social structures, and the level of the human potential [27, pp. 106-109, 102- 105]. Zaslavskaya emphasizes that change of institutions, while being an important result of societal transformations, is not an end in itself but rather an external manifestation of transformations, a tool for achieving deeper ultimate goals. These include changes in the social-group structure of society: the system of social inequalities, the appearance of new social groups, etc. [27, pp. 103-104], in short, processes that are less susceptible to external control and are a consequence of the transformation of key institutions. But the most profound and longterm results of transformation processes are associated with changes in the human potential: “an increase or decrease in this potential is the most fundamental criterion of whether the ongoing transformations lead to the flourishing and renewal of society or to its decline and degradation” [27, pp. 104-105]. A detailed analysis of each coordinate axis of this trihedral prism will be found in a number of works by Zaslavskaya (see [37; 24; 25; 27, pp. 111-187; 41, pp. 317- 387], and others).

In my view, Zaslavskaya also deserves special credit for validating the range of key institutions that should be taken into account in determining the societal type of a given society. Along with the quality of two generally recognized basic institutions such as power (how democratic, legitimate and effective it is) and property (its structure, degree of development, legitimacy, protection), she argues the need to take into account the degree of development of two other (“not conventional”) institutions: first, the diversity and maturity of the structures of civil society, and second, the scope and strength of human rights and freedoms [36, p. 446; 27, p. 120].

Indeed, fundamentally different qualities of civil society and human rights can correspond to one and the same configuration of power and property. For example, it is possible to formally democratize power or quickly liberalize property relations, but to do this by infringing on the real rights of most citizens, in accordance with the rules of the game inherited from the previous administrative-command system [27, p. 121].

The inclusion of these institutions in the results block is important not only for an assessment of the course and results of transformation. It also helps to understand the ambiguity of the relationship between the basic institutions and economic growth. For example, Viktor Polterovich and Vladimir Popov showed that the nature of the impact of democratization on economic growth depends on the conditions in which it takes place: while stimulating economic growth in countries where law and order is strong enough (with a corruption perceptions index higher than 6.65), it has a negative impact on economic growth in countries with poor law and order. Based on a classification of post-communist countries according to the average index of political rights for 1998-2000 as calculated by Freedom house, they found that “partly free” countries (Russia, Ukraine, Croatia, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova) experienced a deeper recession and a larger increase in social inequality than so-called “not free” countries (Belarus, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). In other words, rapid democratization in authoritarian countries with poor law and order can have many negative economic and social consequences [15].

Zaslavskaya’s conception suggests that although the general direction of societal transformation in Russia has been determined, the question of the possible type of market relations and the degree of democracy in the political system is still open. Transformation options may differ significantly in the correlation of different elements: spontaneous or controlled, lawful or unlawful, market or administrative-redistributive, democratic or authoritarian, etc.

The Transformation Structure of Society and the Prospects of Social Transformation

The enrichment of the conceptual framework and tools for studying social transformations based on the development and validation of a new concept— “transformation structure of society” (Block D)—is an important methodological finding that significantly increases the opportunities for a scientific understanding of the mechanisms and pathways of the current transformation process [36, pp. 193-204; 445-465]. This term denotes the system of social macro agents whose interaction (cooperation, competition, struggle) drives the societal transformation of society [36, p. 519; 27, p. 267]. The need to study this structure arises from a desire to understand what social forces—consciously or unconsciously— promote the modernization of the social system or contribute to its stagnation and degradation, what are their interests and internal structure, what are the resources at their disposal, and how they achieve their goals [27, p. 208]. The point is that in order to understand the social mechanism, the driving forces and prospects of social change, it is not enough to know the stratification structure of society. The transformation structure is formed under the impact not only of social stratification, but also of socio-political and cultural differentiation, which reflects the differences in the motivation of agents and the substantive orientation of their transformational activity [36, p. 452]. Whereas the social structure is more concerned with the “anatomy” of society, the transformation structure describes its “physiology,” the mode of its operation and development. Reflecting the systemic quality of society, which is particularly important in periods of radical change (namely, its ability to act as an agent of self-reform and self-development), the transformation structure includes not only active, but also passive groups. “The effectiveness of this structure is determined by the correlation of social forces that help to either deepen and consolidate the liberal-democratic transformations, to maintain and restore Soviet-type institutions, or to undermine the institutional system as such” [27, p. 208]. The measure of this quality is what Zaslavskaya called the innovative-reform potential of society [36, pp. 519-520; 27, p. 208].

The approach to identifying specific elements of the transformation structure of post-communist societies developed by Zaslavskaya is very appropriate. In her conception, this structure has two important projections, which reflect different approaches to identifying the collective macro actors in the transformation process. Under the vertical (social-hierarchical) approach, it is social strata and groups of society with different resource potentials that are seen as such macro actors (cultural and political differences within each hierarchical layer are ignored). The horizontal approach, on the contrary, focuses attention on the cultural- political differentiation of social actors (differences in culture, beliefs, interests, attitudes, and orientation of social action), abstracting from their place in the status hierarchy.

In contemporary Russia, the horizontal projection of the transformation structure includes statist, oligarchic, liberal-democratic, social-democratic, national-patriotic, and criminal (unlawful quasi-political) forces. A prominent role is also played by non-political forces, which include almost half of the population [36, pp. 523-538; 27, pp. 346-350]. The intersection of the vertical and horizontal projections helps to bring out the main elements of the transformation structure. For Zaslavskaya, these are communities with both similar social status and close socio-political and cultural characteristics. Horizontal integration of such communities gives social strata, while vertical integration gives the main cultural-political forces differing in resource potential, social embeddedness and cohesion. Such an approach to identifying the real macro actors in the current transformation process is evidently productive because it allows us to assess both the strength of the social base of the key social forces, the opportunities for their consolidation with each other, and the nature and scale of resources available to them in achieving their purposes. Thus, researchers studying the current transformation process obtain a reliable methodological toolkit for a more valid assessment of the possible and most likely scenarios of social development at different stages of the transformation process.

Zaslavskaya does not simply identify the main cultural-political forces but, viewing them as fragmentary and unstable in modern Russia [27, p. 311], divides them into two groups potentially capable of turning into political alliances competing for power. This division is based on the degree of commonality in value and activity orientations measured by seven criteria (two political, two economic, and an ideological, a legal and a foreign-policy criterion) [27, p. 351]. one group includes statist, social-democratic and communist-patriotic forces, and the other, oligarchic, liberal-democratic and criminal forces. In order to assess the influence of different cultural-political forces and their potential alliances on the transformation of Russian society, Zaslavskaya supplements the horizontal projection of the transformation structure with a vertical one. For this purpose, she identifies the social structure of the followers of various forces, which helps to understand the degree of their social embeddedness (i.e., the depth to which the respective ideas and interests penetrate the mass strata). In addition, she tries to compare them in terms of the approximate amount of resources at their disposal.

Since Russia’s cultural-political forces are still quite vague and the boundaries between them are not always clear, any attempts at a quantitative assessment of the resources at their disposal are futile. That is why Zaslavskaya determines the approximate correlation of these forces based on a qualitative assessment of their resources on a four-point scale (0 points—absence or insignificant amount of a certain resource at the disposal of a particular force, 1 point—limited amount, 2 points—significant amount, and 3 points—very large amount), with subsequent correction of the results taking into account the weights of various resources in the Russian social context (3—political, 2.5—economic, 2— administrative, 2—law-enforcement, 1.5—cultural, and 1—social resources). As a result, the cultural-political forces being analyzed were divided into leading forces, i.e., those that have the most powerful effect on the transformation process (statist and oligarchic), secondary but politically significant (criminal), peripheral (communist-patriotic), and weakest (liberal-democratic and social-democratic) forces [27, p. 392]. considering the composition and correlation of cultural-political forces in Russia, Zaslavskaya came to the conclusion more than 10 years ago (in 2003) that the most likely scenario for the country’s development was the moderate statist scenario [27, pp. 392-398], and this is actually what we see today.

Zaslavskaya’s Contribution to the Current Debate on Social Mechanisms

The activity-structural conception of the social mechanism of the transformation process, which takes into account the interrelation and relative autonomy of different levels of social reality and the interests and resources of actors at different levels and of different types, provides researchers with a reliable methodological toolkit for a more valid assessment of the possible and most likely scenarios of social development at different stages of the transformation process and for a deeper understanding of the patterns and regularities of post-communist transformations. The application of mechanismic methodology to an analysis of specific (compared to society as a whole) transformation processes has also proved to be productive,1 as well as its application to the study of the spread and institutionalization of new social practices, including unlawful ones [27, pp. 256- 263; 43, pp. 3-38; 49, pp. 208-261].

The original analytical scheme of the social transformation mechanism facilitates interdisciplinary interactions and promotes comparative studies in different post-communist societies. An understanding of the structure of social mechanisms that drive current economic and social processes is of great practical importance, helping managers and executives at different levels to make more effective management decisions.

Based on a solid empirical foundation, on a constant and close integration of theory and empirical research, Zaslavskaya’s conception helps to clarify a number of epistemological questions regarding the category of social mechanism that are being raised today in Western social thought. In particular, there is no reason to associate the idea of social mechanism exclusively with the principle of methodological individualism as some authors do [6, p. 298]. A mechanism-based explanation is quite compatible with different theories of social action [14, p. 248; 19, p. 58-59; 5, p. 363]. In Zaslavskaya’s conception, much importance is given to the value orientations of individuals, the cultural norms they share, and the scale and structure of resources available to them (political, administrative, economic and social, including image; network power, etc.) [27, p. 389-390].

Zaslavskaya’s conception of social mechanisms supports the position of those theorists who say that it would be a “fateful misunderstanding” to believe that macro phenomena follow directly from motivated individual behavior [14, p. 249; 5, p. 369]. Between Block A and Block c, she places Block B called “Mass transformation processes” (see Figure 1), which “appear to have no agents: formally, no one is responsible for their course, but actually all are responsible.” And it is precisely this set of poorly controlled, intertwined mass processes involving multiple social actors of different types (ranging from individuals and small groups to corporations and government bodies) that serves as a direct “tool” for changing the societal characteristics of society (arrows 1, 2, 3). examples of mass transformation processes include the emergence of a competitive labor market, the development of business, the spread of corruption and moonlighting, the rise of the protest movement, income polarization, etc. [33, p. 293]. Many properties of the social system are emergent properties [16, p. 272].

At the same time, the conception of the social mechanism of the transformation process also distances itself from purely objectivist conceptions, which emphasize the role of some kind of deterministic laws while neglecting any intentional actions of individuals whatsoever and the properties of their consciousness. The poor controllability of the transformation process, the important role of spontaneous factors in its development, and its indeterminate results point to the probabilistic nature of the regularities underlying social mechanisms. In the study of real-life social and economic processes, undue emphasis is placed on the debate about whether the initial conditions (“inputs”) and results (“outputs”) should be included in the formal definition of social mechanism. In Zaslavskaya’s conception, Block c (“mechanism proper”) is the key block, but it would be left hanging in the air unless it became an element of a holistic (systemic) view of the transformation process, a view based on a certain theoretical notion of the main blocks, their elements, and their internal and external relationships. Application of the conception of the social mechanism of the transformation process to more specific processes naturally makes it necessary to specify the main blocks and relationships. Zaslavskaya admits that concepts such as “social mechanism of economic development” or “social mechanism of the transformation process” are scientific abstractions because in reality these processes, like any other macro phenomena, are regulated by multiple mechanisms “responsible” for more specific processes. In fact, each block (element of a block) and the key relationships between them are the outcome and process of the operation of a number of specific mechanisms.

The study of the mechanisms of various phenomena is a more complex process than the study of their factors. It derives from a sense of dissatisfaction with attempts to establish the nature of the relationship between variables without an attempt to understand the “cogs and wheels” that ensure this relationship. But contrasting “mechanismic” and correlation analysis in a categorical way is not always justified and should not go too far. Modern methods of mathematical statistical analysis and computer simulations can be very helpful in studying mechanisms and in verifying the explanatory models developed by researchers. In short, they can serve as a constructive supplement to “mechanismic” analysis. The promising nature of the category of social mechanism developed by Zaslavskaya is also confirmed by the fact that today it is used by a wide range of social scientists and has become a key element of research methodology not only at NESSh, but also in a number of other sociological communities (see, for example, [21; 18]).

***

Today, some propositions of the conception have yet to be verified empirically in the course of extensive research. Such a task cannot be accomplished by a single researcher. In a situation of data scarcity, Zaslavskaya tried to address research problems by summarizing the results of numerous studies, based on her own experience and expert assessments. This enabled her to correctly discern the most likely scenarios of the transformation process in Russia. But considering the new conditions and new processes, there will come a time for representative studies of the elements and relationships of the transformation structure of society, the correlation of different types of transformational activity, etc. The identification and analysis of social mechanisms is now recognized as a question of great importance both for the development of social sciences and for enhancing the effectiveness of management decisions. As I see it, the future role of mechanism-based analysis is particularly important in transforming economies and societies. Zaslavskaya’s conception of social mechanisms, which is used to explain the patterns and regularities of real social change, provides future researchers with effective and relevant theoretical and methodological tools for further exploratory research and progress, and gives practitioners an important instrument for developing balanced and effective strategies.

References

1. Aakvaag G. C. Social Mechanisms and Grand Theories of Modernity—Worlds Apart? 56, No. 3.

2. Anderson P. J. J., Blatt R., Christianson M. K., Grant A. M., Marquis C., Neuman E. J., Sonenshein S., Sutcliffe K. M. Understanding Mechanisms in Organizational Research: Reflections from a Collective Journey. Journal of Management Inquiry. 2006. vol. 15, no. 2.

3. Goryachenko Ye. Ye. Territorial Aspect of the Social Mechanism of Economic Development. Ways to Improve the Social Mechanism of the Development of the Soviet Economy. Novosibirsk, 1985. (in Russian).

4. Goryachenko Ye. Ye. Territorial Community in a Changing Society. The Social Trajectory of Reforming Russia: Studies of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology. Novosibirsk, 1999. (in Russian).

5. A Pragmatist Theory of Social Mechanisms. American Sociological Review.2009. Vol. 74, No. 3.

6. Hedstrom P., Swedberg R. Social Mechanisms. Acta Sociologica. 1996. Vol. 39, No. 3.

7. Hedstrom P., Ylikoski P. Causal Mechanisms in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010. Vol. 36.

8. Kaidesoja T. Overcoming the Biases of Microfoundationalism: Social Mechanisms and Collective Agents. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2013. vol. 43, No. 3.

9. Kalugina Z. I. The Social Mechanism of the Development of Subsidiary Household Plots. Abstract of a Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Science (Sociology). Novosibirsk, 1991. (in Russian).

10. Kalugina Z. I. Subsidiary Household Plots in the USSR: Social Regulators and Development Results. Novosibirsk, 1991. (in Russian).

11. Kosals l. Ya. The Social Mechanism of Innovation Processes. Novosibirsk, 1989.

12. Mahoney J. Beyond Correlational Analysis: Recent Innovations in Theory and Method. Sociological Forum. 2001. Vol. 16, No. 3.

13. Mason, K., Easton, G., lenney P. Causal Social Mechanisms; from the What to the Why. Industrial Marketing Management. 2013. vol. 42, no. 3.

14. Mayntz R. Mechanisms in the Analysis of Social Macro-Phenomena. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2004. Vol. 34, No. 2.

15. Polterovich V. M., Popov V. V. Democratization and Economic Growth. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2007. no. 2.

16. Sawyer R. K. The Mechanisms of Emergence. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2004. Vol. 34, No. 2. Social-Management Mechanism of the Development of Production. Methodology, Methods and Results of Research. Novosibirsk, 1989. (in Russian).

18. Sokolova G. N. Economic Sociology. Minsk, 2001. (in Russian).

19. Steel D. Social Mechanisms and Causal Inference. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2004. Vol. 34, No. 1.

20. Weber E. Social Mechanisms, Causal Inference, and the Policy Relevance of Social Science. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2007. Vol. 37, No. 3.

21. Yakuba Ye. A. Sociology. Kharkov, 1998. (in Russian).

22. Zaslavskaya T. I. Behavior of Mass Social Groups as a Factor of Social Transformation. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskiye i sotsialnye peremeny. 2000. No. 6.

23. Zaslavskaya T. I. The Business Stratum of Russian Society: Essential Features, Structure, and Status. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 1995. No. 1.

24. Zaslavskaya T. I. exploration of the Mechanisms of Social processes (1981-1985). The Social Trajectory of Reforming Russia: Studies of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology. Novosibirsk, 1999. (in Russian).

25. Zaslavskaya T. I. the human potential in the current transformation process. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2005. no. 3, no. 4.

26. Zaslavskaya T. I. the innovative-reform potential of Russia and the problems of civil Society. The Innovative-Reform Potential of Russia and the Problems of Civil Society. Moscow, 2001. (in Russian).

27. Zaslavskaya T. I. Modern Russian Society: Social Transformation Mechanism. Moscow, 2004. (in Russian).

28. Zaslavskaya T. I. New Generation of Actors in the Russian Economy: Problems of Social Quality. Obshchestvo i ekonomika. 2005. no. 5.

29. Zaslavskaya T. I. On the Social Actors in the Modernization of Russia. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2011. No. 3.

30. Zaslavskaya T. I. On the Social Mechanism of Economic Development. Ways to Improve the Social Mechanism of the Development of the Soviet Economy. Novosibirsk, 1985. (in Russian).

31. Zaslavskaya T. I. On the Social Mechanism of Post-Communist Transformations in Russia. Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (SOTSIS). 2002. no. 8.

32. Zaslavskaya T. I. On the Social Transformation Structure of Society. Obshchestvo i ekonomika. 1998. No. 3-4.

33. Zaslavskaya T. I. Russian Society at a Social Turning Point: A View from Inside. Moscow, 1997. (in Russian).

34. Zaslavskaya T. I. Selected Works. Vol. 2. The Transformation Process in Russia: In Search of a New Methodology. Moscow, 2007. (in Russian).

35. Zaslavskaya T. I. Social Mechanism of the Transformation of Russian Society. Sotsiologichesky zhurnal. 1995. No. 3.

36. Zaslavskaya T. I. Societal Transformation of Russian Society. Activity-Structural Conception. Moscow, 2002. (in Russian).

37. Zaslavskaya T. I. The Transformation Process in Russia: Socio-Structural Aspect. The Social Trajectory of Reforming Russia: Studies of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology. Novosibirsk, 1999. (in Russian).

38. Zaslavskaya T. I. The Vanguard of the Russian Business Community: Gender Aspect. Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (SOTSIS). 2006. No. 4, No 5.

39. Zaslavskaya Т. I. A Voice of Reform. New York, London, 1989.

40. Zaslavskaya T. I., Gromova R. G. On the “Middle Class” in Russian Society. Mir Rossii. 1998. No. 4.

41. Zaslavskaya T. I., Krylatykh E. N., Shabanova M. A. New Generation of Business People in Russia. Moscow, 2007. (in Russian).

42. Zaslavskaya T. I., Ryvkina R. V. The Sociology of Economic Life. Essays in Theory. Novosibirsk, 1991. (in Russian).

43. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. On the Problem of Institutionalization of Unlawful Social Practices in Russia: Sphere of Labor. Mir Rossii. 2002. No. 2.

44. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. Social Mechanisms of Institutionalization of Unlawful Social Practices. The Russia We Are Gaining. Studies of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology. Novosibirsk, 2003. (in Russian).

45. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. Social Mechanisms of Transformation of Unlawful Practices. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2001. No 5.

46. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. The Spread and Institutionalization of Unlawful Practices in the Sphere of Labor and Employment. The Russia We Are Gaining. Studies of the Novosibirsk School of Economic Sociology. Novosibirsk, 2003. (in Russian).

47. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. Successful Economic Actors as a Potential Modernization Community. Article 1. Social peculiarities and interactions in a problematic institutional environment. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2012. No. 4.

48. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. Successful Economic Actors as a Potential Modernization Community. Article 2. The Innovation Potential and the Problems of its Realization. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost (ONS). 2012. no. 5.

49. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. The Transformation Process in Russia and the Institutionalization of Unlawful Practices. Origins: Economics in the Context of History and Culture. Moscow, 2004. (in Russian).

50. Zaslavskaya T. I., Shabanova M. A. Unlawful Labor Practices and Social Transformations in Russia. Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (SOTSIS). 2002. no. 6.

Notes

- For example, Leonid Kosals studied the social mechanism of innovation processes; Zemfira Kalugina, the functioning and development of the household sector in the agro-industrial complex; a team led by Rozalina Ryvkina, the vertical components of the social-management structure of the agroindustrial complex; Yelizaveta Goryachenko’s team, the territorial aspects of the social mechanism, etc. (see, for example, [11; 9; 10; 17; 3; 4]).

Translated by Irina Borisova