*This article was supported by a Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, “Collected Research on Non-Published Chu Slips (Five Types) Unearthed in Hubei Province” (No. 10&ZA089), and the research study “Preservation, Heritage and Design of Traditional Chinese Clothing” sponsored by the Doctoral Talent Cultivation Project for Serving Special National Needs.

The Qin dynasty slip manuscripts in the collection of Peking University (hereafter referred to as the “PKU Qin slips”) include a manuscript entitled Making Clothes [Zhiyi 制衣], comprising 649 extant characters on 27 slips.[1] The phrase “making clothes” appears often as a title of sections of technical manuscripts of the Warring States period, the Qin empire [which later became a dynasty – Trans.] and the Han dynasty; the contents of such manuscripts always relate to the selection of a day and time for producing clothing. The Making Clothes text in the PKU Qin slips, however, is a technical work on the making of skirts [qun裙], jackets [shangru 上襦], outerwear [daru 大襦], and trousers [ku 袴] and is not related to calculation techniques in the least. The collation team of the PKU Qin slips holds that this corpus dates to around the time of Emperor Shihuangdi of the Qin dynasty.[2] Based on its contents, one may further limit the likely time of composition of the Making Clothes text. The tailoring designs described in Making Clothes assume a cloth width of two chi five cun [one chi was equivalent to 23.1 centimeters and one cun was equivalent to 2.31 cm in the Qin dynasty – Trans.], a figure originally stipulated in the Qin “Statutes on Currency and Fabrics.”[3] The Qin laws recovered from the Qin dynasty tombs at the Shuihudi site may date to as early as the late Warring States period,[4] and Making Clothes was probably composed at roughly the same time.

Judging from the text’s statement “This is a description of the craftsmanship of Huang Ji” [此黄寄裚(制)述也], this document records tailoring techniques taught by a certain Huang Ji.[5] Neither this figure nor their disciples appears in historical records.[6] The appearance of Making Clothes has filled an important gap in the textual records of early Chinese tailoring techniques. For this reason, the book is of profound value to the study of the history of ancient clothing.

This essay focuses on the treatment of “skirts” and “trousers” in the Making Clothes text. It analyzes their structure and the tailoring methods used in their construction, and it briefly discusses related questions. The authors welcome reader comments.

STRUCTURE AND TAILORING OF SKIRTS

The first section of Making Clothes is arranged in paragraphs, transcribed as follows:

大衺四幅,初五寸、次一尺、次一尺五 寸、次二尺,皆交窬,上为下=为上,其短长 存人。

中衺三幅,初五寸、次一尺、次一尺五 寸,皆交窬,上为下=为上,其短长存人。

少衺三幅,初五寸、次亦五寸、次一 尺,皆交窬,上为下=为上,其短长存人。

此三章者,皆帬(裙)裚(制)也,因以 为衣下帬(裙)可。

[Translation of inscription]

The large diagonal-cutskirt[xie 衺] uses four bolts of cloth. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next at 1 chi, the next at 1 chi 5 cun,and the next at 2 chi. All are cut diagonally [jiaoyu 交窬], with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top [see explanation in Section A below – Trans.]. The length follows [depends on] that of the person.

The medium diagonal-cutskirtuses three bolts of cloth. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next at 1 chi, and the next at 1 chi 5 cun. All are cut diagonally, with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The length follows that of the person.

The small diagonal-cutskirtuses three widths of fabric. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next again is measured at 5 cun, and the next at 1 chi. All are cut diagonally, with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The length follows that of the person.

All three of these methods produce skirts, and may thus be used to make skirts for use as lower garments.

The above paragraphs have no original chapter name, but their contents deal with the methods of tailoring and styles of skirts. The character 帬 [qun] employed in the manuscript is equivalent to 裙 [qun], which is listed in Explaining and Analyzing Characters under “The Jin Radical” [Jinbu 巾部]. This text notes: “帬 is a lower-body garment.”[7] Duan Yucai comments, “Concerning the old character 帬… That a lower garment [chang 常(裳)] is called “lower skirt” [xia qun 下帬] shows that a skirt [帬] is below. Moreover, one gathers together several bolts of fabric in order to make it, just as a skirt [帬] gathers together several widths to cover the body.”[8] The skirt[帬] referred to in the manuscript was a covering garment for the lower body produced by assembling several bolts of fabric. It could be linked or otherwise paired with a garment for the upper body and so is also called a “lower skirt.”

The manuscript Making Clothes divides skirts into the categories of large, medium-sized, and small diagonal-cutskirts[xie 衺]. The character 衺 is also written as 邪 [xie], as noted in Duan Yucai’s commentary to the “The Yi Radical” [Yibu 衣部] chapter of Explaining and Analyzing Characters: “The character 衺 is currently written 邪.”[9] The commentary also notes, “All upper and lower garments that are not cut diagonally [衺] are called duan [褍].”[10] Does the manuscript’s use of the term xie for all skirts indicate that they were produced with diagonally-cut fabric? When it comes to the techniques of skirt tailoring, the term jiaoyu is key to understanding their structures. Li Liu holds that jiaoyu refers to a cutting technique mentioned in the tailoring of skirts, jackets [ru 襦], and trousers, like the phrase jiaoshu [交输, curved hem cross-wrapping in the back] that appears in the “Biographies of Kuai Wu and Jiang Xifu” section of the Book of Han: “Wearing a yarn silk gauze casual gown, with jiaoshu,” it refers to cutting diagonally.[11] This is undoubtedly correct. The meaning of jiaoyu corresponds with the term xie in the three styles of skirt mentioned in the manuscript, which indicates diagonal-cut tailoring.[12] Described in simple terms, a complete, rectangular piece of fabric was cut diagonally from short edge to short edge, yielding two long, congruent trapezoidal pieces containing one right angle each. The three styles of skirt that the manuscript describes were all in the jiaoyu fashion, i.e., composed of pieces produced with this method.

(A) Structure of the Large Diagonal-Cut Skirt

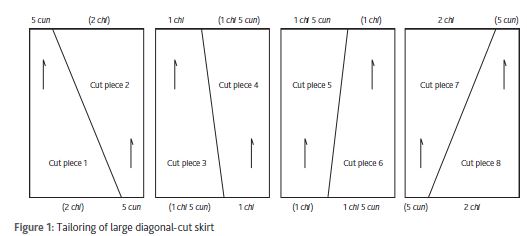

The manuscript Making Clothes records, “The large diagonal-cut qun-skirt is composed of four bolts of cloth. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next at 1 chi, the next at 1 chi 5 cun, and the next at 2 chi. All are cut diagonally (jiaoyu), the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The length follows that of the person.”[13] From this we can deduce that the “large diagonal-cut qun-skirt” was tailored from four complete bolts of fabric cut diagonally in the jiaoyu style to produce eight pieces. The expression “The top being the bottom and the bottom being the top” means that each rectangular piece of fabric was cut symmetrically into two trapezoids, which matched identically when one was inverted top-to-bottom. The statutory width of fabric bolts in the Qin dynasty was 2 chi 5 cun, and the first bolt was cut beginning at a point 5 cun in (leaving a width of 2 chi); the second beginning at 1 chi (leaving a remaining width of 1 chi 5 cun); the third at 1 chi 5 cun (leaving a remaining width of 1 chi); and the fourth at 2 chi (leaving a remaining width of 5 cun (Figure 1).[14]

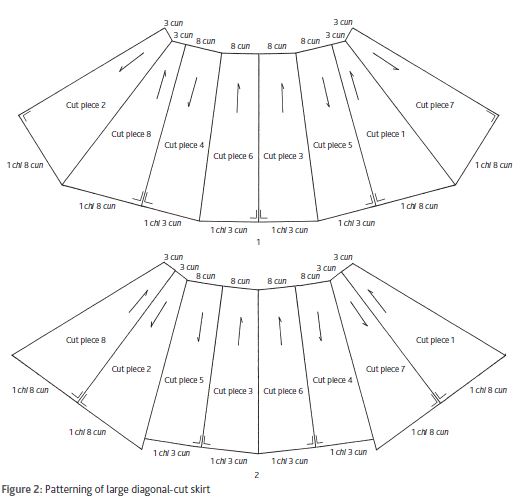

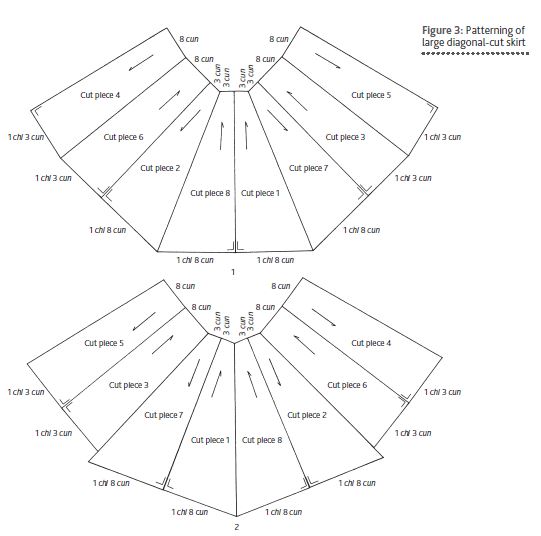

Structurally speaking, the large diagonal-cut skirt was composed of eight right-angled trapezoids in pairs. The eight narrow edges made up the waist portion of the skirt, while the eight wide edges formed the hemline. How were these eight pieces sewn together into a complete skirt? Based on the sewing principle of “straight threads against straight threads, angled threads against angled threads,” there are four structural models for patterning the skirt (Figures 2 and 3).[15]

In Patterns 2 (Figure 2:2) and 4 (Figure 3:2), pieces with diagonal edges of different lengths are paired together. The completed skirt thus lacks a sense of fine workmanship, and the differing angles of the threads in the diagonal edges add to the technical difficulty of sewing required to produce the piece. Because of this, these two patterning models should be ruled out. Patterns 1 (Figure 2:1) and 3 (Figure 3:1), in which the full body of the skirt appears relatively open, smooth and natural, are more likely possibilities. The fan-like curvature of Pattern 3 is relatively pronounced, and the center line pairs straight threads with straight threads; the overall shape of Pattern 1 is relatively straight, and the center line likewise matches straight threads with straight threads. Since the curvature of the top edge of Pattern 3 is relatively pronounced, the waist opening would, when positioned around a wearer’s waist, create natural, wavy folds along the hem of the skirt that would facilitate movement of the lower limbs.[16] Since, on the other hand, the top edge of Pattern 1 is relatively straight, the hem of the resulting skirt would be relatively smooth and more fitted.

The waist measurement of the–skirt as produced according to either Pattern 1 or Pattern 3 would be 4 chi 4 cun, while the hem circumference would be 1 zhang [equivalent to 231 cm in the Qin dynasty – Trans.] 2 chi 4 cun. Since the Qin dynasty value for one chi was 23.1 cm,[17] the waist of the large diagonal-cut skirt would measure 101.6 cm and the hem 286.4 cm. The hem edge of the large diagonal-cut skirt would thus be 2.8 times as long as the waist edge, a ratio greatly exceeding the guideline that the hem of a shenyi-casual gown [shenyi 深衣] should have a circumference twice that of the waist.[18]

(B) Structure of the Medium Diagonal-Cut Skirt

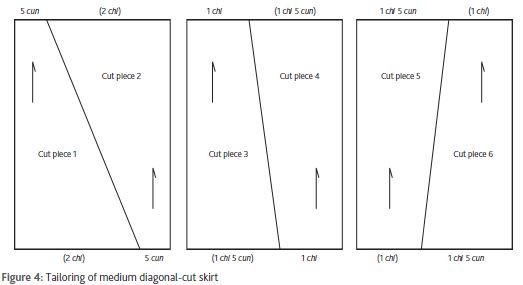

The manuscript Making Clothes records, “The medium diagonal-cut skirt uses three bolts of cloth. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next at 1chi, and the next at 1 chi 5 cun. All are cut diagonally, with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The length follows that of the person.” From this we can learn that the “medium diagonal-cut skirt” was produced by cutting three bolts of fabric along a lengthwise diagonal in the jiaoyu style to produce six right-angled trapezoids, with the two pieces produced from each width sharing identical measurements. Following the guideline of a width of 2.5 chi, the first bolt was cut beginning at a point 5 cun in (leaving a width of 2 chi on the top edge); the second beginning at 1 chi (leaving a remaining width of 1 chi 5 cun); and the third at 1 chi 5 cun (leaving a remaining width of 1 chi) (Figure 4).

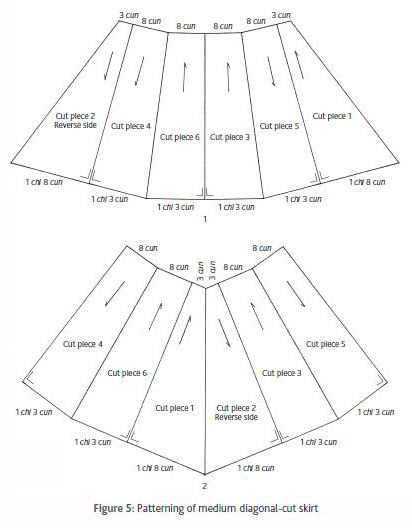

Following the sewing principle that straight threads should be matched with straight threads, angled with angled, and referring to the patterning of the large diagonal-cut skirt, one may propose two different patterning models for the medium diagonal-cut skirt (Figure 5).

The differences between these two models are fairly substantial. Pattern 1 (Figure 5:1) would yield a relatively straight shape with straight threads meeting at the center line, while Pattern 2 has a curved fan shape with angled threads meeting at the center line. Both the waist edge and the hem of pattern 2 have a relatively pronounced curve compared with Pattern 1, such that the body of the skirt would produce an undulating wave when rendered in three dimensions. As required by the overall shape of the pattern, the second cut piece of the medium skirt would be different from the other pieces, requiring the artisan to use the reverse side of the material.

Compared with the large version, the measurements of the medium diagonal-cut skirt would have been relatively small. The waist would measure 3 chi 8 cun (87.8 cm), while the hem would measure 8 chi 8 cun (203.3 cm), or approximately 2.3 times the circumference of the waist. The waist opening of the medium skirt was thus 13.8 cm smaller than that of the large skirt, while the hem circumference was reduced by 83.1 cm, rendering the overall size of the garment smaller.

(C) Structure of the Small Diagonal-Cut Skirt

As the manuscript states, “The small diagonal-cut skirt uses three widths of fabric. The first is measured at 5 cun, the next again is measured at 5 cun, and the next at 1 chi. All are cut diagonally, with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The length follows that of the person.” From this one can see that the cutting pattern of the small diagonal-cut skirt resembles that of the medium version. It likewise follows the principle of “the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top,” comprising six pieces cut diagonally in the jiaoyu style from three bolts of fabric. Given the standard width of 2.5 chi, the first bolt of fabric was cut beginning at a point 5 cun in (leaving a remaining width of 2 chi); the second would also be cut at 5 cun (leaving a remaining width of 2 chi); and the third at 1 chi (leaving a remaining width of 1 chi 5 cun) (Figure 6).

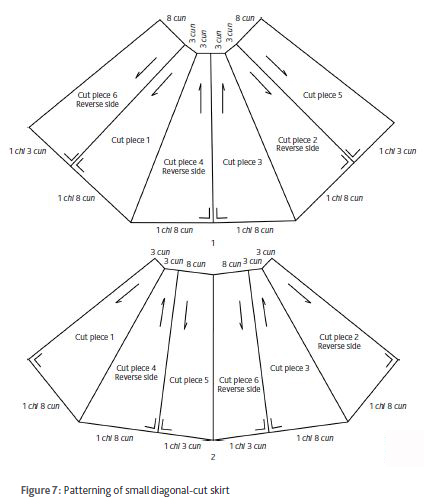

By referring to the patterning of the large and medium versions, as well as the principle of matching straight threads to straight threads and angled to angled, one may see that there are two possible patterning models for the small diagonal-cut skirt (Figure 7). These two models are quite different in style. Pattern 1 (Figure 7:1) forms a fan shape with a relatively strong curvature; its waist edge is quite curved, and straight threads meet at its center line. Pattern 2 (Figure 7:2) forms a comparatively straight fan shape; its waist edge is almost straight and angled threads meet at its center seam. When rendered in three dimensions, the two patterns would differ in their degree of natural folds. The structure of the small diagonal-cut skirt requires using the reverse side of three cut pieces, namely pieces 2, 4 and 6.

Based on calculations, the waist circumference of the small diagonal-cut skirt would measure 2 chi 8 cun (64.7 cm), while the hem circumference would be 9 chi 8 cun (226.4 cm), making the hem circumference approximately 3.5 times that of the waist. As compared with the medium version, the small skirt has a waist 23.1 cm smaller, while the hem circumference exceeds that of the medium version by 23.1 cm. Overall, the waist of the skirt becomes smaller from the large to the small versions; however, the hem circumference is somewhat different, in that the medium skirt has the smallest hem circumference of the three.

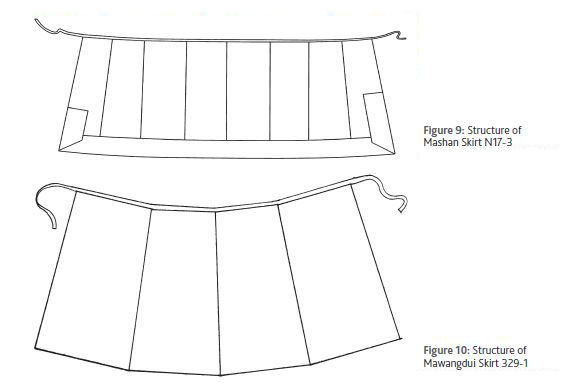

Each of the skirts described in Making Clothes has a notable characteristic, namely the relatively large difference between the width at the waist and the hem (also called the “hem increment”); the larger this figure is, the larger the hem opening of the finished garment will be. The differential values for the large, medium and small skirts described in Making Clothes are 184.8 cm, 115.5 cm and 161.7 cm, respectively. These greatly exceed the respective values of 30.5 cm and 48 cm for the dark yellow silk skirt with item number N17-3 from Chu Tomb M1 at the Mashan site in Jiangling County, Hubei Province (hereafter abbreviated as “Mashan Skirt N17-3”) and the skirt with item number 329-1 from Han Tomb M1 at the Mawangdui site in Changsha City (hereafter abbreviated as “Mawangdui Skirt 329-1”).[19] Apart from aesthetic factors, this type of design seen in Making Clothes could support a wide range of motion for the lower limbs, fulfilling the needs of a laborer or infantry soldier.

(D) Practical Examples of the Making Clothes Style of Skirt

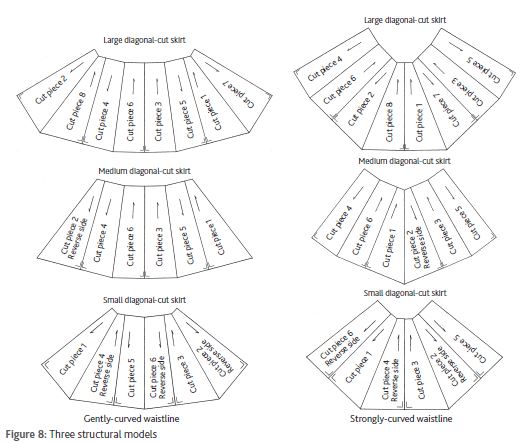

The three types of skirts described above can be logically divided into two types: a “strongly curved waistline” type and a “gently curved waistline” type, each of which is represented in large, medium and small versions (Figure 8). The “strongly curved” type would have presented a relatively good result once rendered in three dimensions on a wearer, with a wave patterning at its hem. The “gently curved” type would have been relatively smooth and fitted when worn.

Which of these two types would have been more practical? Or could it be that both were used? Chu Tomb M1 at the Mashan site yielded two skirts of identical shape. Mashan Skirt N17-3, taken here as an example, is 82 cm long, 181 cm in waist circumference, and 211.5 cm in hem circumference. The surface of the skirt is made up of eight pieces, smaller at the top than at the bottom, yielding a fan-shaped structure (Figure 9). The widths of the pieces at the hem edge measure 27 cm, 27 cm, 27.5 cm, 26 cm, 27 cm, 24 cm, 27 cm and 26 cm. The hem measures 12.5 cm deep.[20] The middle pieces have relatively small hem measurements, while the outside pieces have relatively large hem measurements. The cut pieces were generally about half the full width of a standard piece of fabric.

Han Tomb M1 at the Mawangdui site contained two skirts of identical form, each comprising four silk pieces of one full width sewn together. All pieces were narrower at the top and wider at the bottom. The two middle pieces were of relatively the same narrow width, while the two outside pieces were also identical in width, but relatively broader. Skirt 329-1, taken here as an example, measures 87 cm long, 145 cm in waist circumference, and 193 cm in hem circumference, with a waistband ranging from 2 cm to 2.8 cm wide (Figure 10).[21]

Comparison shows that the difference in hem and waist circumference of the above two skirts is much less pronounced than that of each of the Making Clothes skirts. The hem of Mashan Skirt N17-3 is 1.2 times greater in circumference than its waist opening, while Mawangdui Skirt 329-1 shows a ratio of 1.3; both values fall far short of the range of 2.3 to 3.5 observed in the Making Clothes skirts. Evidently, the “A” shape formed by completed versions of the Making Clothes skirts would be much more distinct. Mashan Skirt N17-3 and Mawangdui Skirt 329-1 both belong to the “gently curved” style, though the waistline of the latter is slightly more curved. Mawangdui Skirt 329-1 followed a principle of putting the pieces with a longer hem edge in the middle and those with a shorter hem edge toward the outside. This characteristic is along the same logical line as the patterning of the “strongly curved” type. (Since the number of pieces and the hem dimensions of the Mawangdui skirt are smaller than those of the Making Clothes skirts, the overall form of the former still belongs to the “gently curved” type, although its patterning method is the same as that used in the latter.) The patterning principle followed in Mashan Skirt N17-3, in which pieces with shorter (or no) hem edges were placed in the middle and those with longer hem edges were placed to the side, independently follows the same logical principle as the “gently curved” type. Evidently, both models saw use among pre-Qin and early Han skirts. This would seem to confirm that both of the skirt types represented in Making Clothes were viable for practical use.

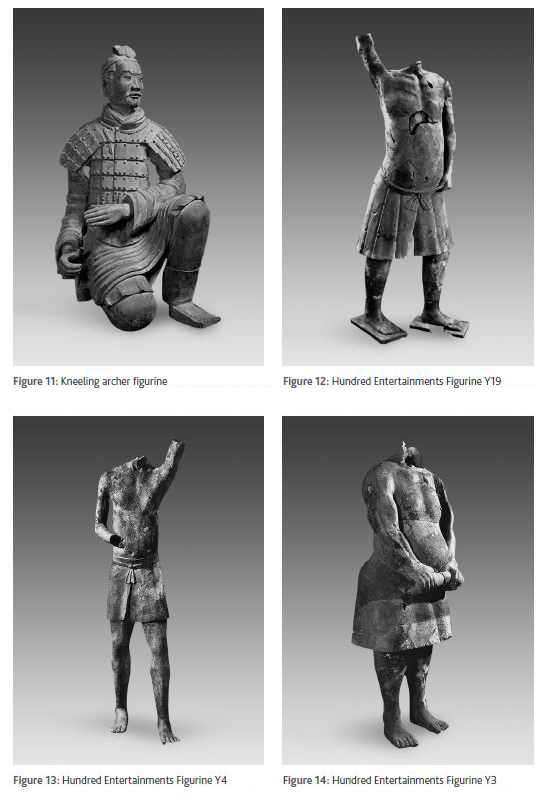

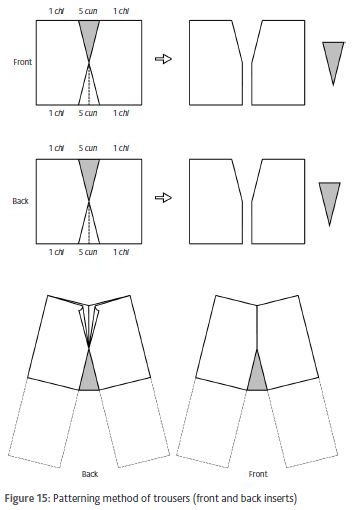

The terracotta warriors of the tomb of Emperor Shihuangdi of the Qin empire have provided objective evidence concerning the clothing styles of the Qin populace. A kneeling archer figurine, recovered from Pottery Warriors and Horses Pit 2 at Emperor Shihuangdi’s mausoleum complex in Lintong District of Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province (Figure 11),[22] is clad in a thick, long jacket with a suit of level-waisted armor; on its lower body, it wears a short skirt, trousers and shallow-mouthed shoes. In the knee area of both legs, it can clearly be seen that the edge of the battle skirt the figurine is wearing forms undulating folds, a characteristic that provided Qin soldiers the necessary space for movement when kneeling and standing. As discussed above, the skirts of the “strongly curved waistline” type all produce wave patterns in their assembled forms, much like that shown in this kneeling soldier figure. Considering the practical demands of war, this skirt, as a likely exemplar of the “strongly curved” type of the large diagonal-cut skirt, would be quite suitable. The “Hundred Entertainments,” i.e., Entertainers Pit K9901 of Emperor Shihuangdi, yielded several pottery figurines that provide direct evidence on the structure of Qin skirts. This variety of figurine has a bare upper body and wears a short skirt cinched with a belt. Figurine Y19 is in a standing position with the right hand raised. Its squared shoulders and protruding belly lend it a sense of vigor. The structure of its short skirt is clearly observable. The hem of the skirt, which falls at the figurine’s knees, has several wavelike pleats (which develop gradually from the waistline to the hem). The style of the skirt tends toward the “strongly curved” type (Figure 12). Figurine Y4 wears a relatively short skirt, the outer surface of which appears smooth and lacks any obvious ripples or folds; its style, obviously different from that of the former case, belongs to the “gently curved” type (Figure 13).[23] Figurine Y3 shows a perfectly round belly, and the construction of its skirt is analogous with that of Figurine Y4, but, more significantly, it also belongs to the “gently-curved waistline” type (Figure 14).

STRUCTURE AND TAILORING OF TROUSERS

(A) Patterning Methods and Restoration of Original Structure

The last portion of Making Clothes reads:

裚(制)绔长短存人。子长二尺、广二尺五寸而三分,交窬之,令上为下=为上。羊枳毋长数。人子五寸,其一居前左,一居后右。此黄寄裚(制)述也。

[Translation]

In making trousers, the length follows that of the person. The fabric used for the crotch [zi 子] is 2 chi long and 2 chi 5 cun wide and is divided into three parts. Cut it diagonally [i.e., in the jiaoyu style], with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top. The “sheep’s limbs” [yangzhi 羊枳] lack a length figure. The crotch insert [renzi 人子] is 5 cun. One occupies the front left, and one the back right. This is the construction technique of Huang Ji.

First let us briefly explain some points of technical vocabulary.

The character 绔 [ku] is an old form of 袴 [ku, trousers]. “The Xi Radical” [Xi bu 糸部] section of Explaining and Analyzing Characters says, “绔 is a garment for the legs,” and Duan Yucai’s commentary notes, “This is what is referred to now as ‘sheath trousers’ [taoku 套袴]. There is one part each for the left and right, divided into a garment for each leg. What was formerly called ku [绔] was also called qian [褰] or duo [襗].”[24]

The term 子 [zi] here indicates a portion of a set of trousers, i.e., the crotch and seat area. The statement “The crotch is 2 chi long and 2 chi 5 cun wide” refers to the dimensions of the piece of fabric used to make the upper part of the trousers. The “three parts” refers to cutting the aforementioned piece of fabric into three parts, though not necessarily three even parts.

In the term 羊枳 [yangzhi], the 枳 [zhi] can be read as 肢 [zhi, limb]. Qin and Han dynasty daybooks contain the phrase 反支 [fanzhi]; a bamboo daybook manuscript from the Qin tombs at Shuihudi writes “反枳 [fanzhi],” to be read as “反支.”[25] The phrase 羊枳 (or 肢) refers to the portions of the trouser legs located below the crotch. Since Eastern Zhou and Qin trousers were often made with bunched openings, the legs of the trousers were broader above and narrower below, like the legs of a sheep. The phrase “The ‘sheep’s limbs’ lack a length figure” means that there was no fixed length for the legs of the trousers; that measurement depended on the stature of the wearer.

The phrase 人子 [renzi] refers to the crotch insert of the trousers. It is in the shape of an isosceles triangle, so its outline resembles the character 人. The statement “The crotch insert is 5 cun” indicates that the lower edge of the insert should measure 5 cun long. From the expression “the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top,” one may determine that the height of this triangular insert is half that of the fabric, i.e., 1 chi.

As for the phrase “One occupies the front left and one the back right,” one may surmise from this text that the trousers were to have a front and a rear crotch insert. One may further infer that the crotch/seat portion [zi 子] was cut alternately in two pieces, so that it had front and rear sections. The two crotch inserts were placed front and rear and sewn together to form a horizontal crotch.

As with the skirts discussed above, the manuscript only records the key point concerning trousers: the patterning of the crotch. It does not discuss the waist or legs. The text therefore only supports the reconstruction of the structure of the crotch area; concerning the rest of the trousers, one can only speculate based on consultation of related materials.

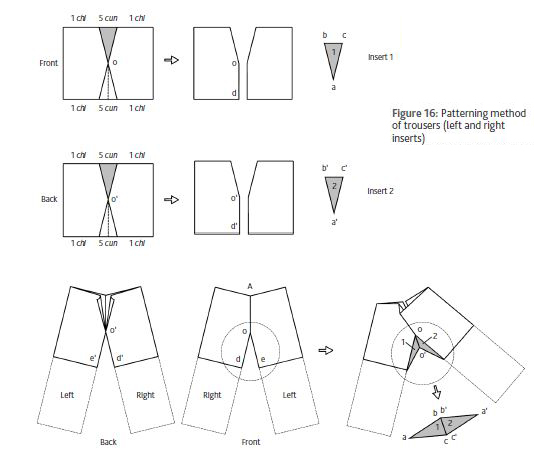

The text states: “The fabric used for the crotch is 2 chi long and 2 chi 5 cun wide and is divided into three parts. Cut it diagonally [i.e., in the jiaoyu style], with the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top.” This indicates the method of patterning the crotch of the trousers. A length of fabric measuring 2 chi was selected; assuming that the fabric width was the standard 2 chi 5 cun, the piece would form a rectangle measuring 2 chi 5 cun by 2 chi. The necessary conditions of the cutting were as follows: The long edge “had three divisions”; the fabric was cut diagonally; and the shape and size should be symmetrical, with “the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top.” Thus, the top and bottom edges of the piece, both measuring 2 chi 5 cun, were marked at points measuring first 1 chi, then 5 cun further in from the corner, dividing the piece into three sections measuring 1 chi, 5 cun and 1 chi wide, respectively. These were the same top to bottom. A diagonal line was then made connecting the first cutting point on the top edge of the piece (the 1 chi mark) with the second cutting point on the bottom edge (the 5 cun mark). A similar line was then made between the second point on the top edge of the piece (the 5 cun mark) and the first cutting point on the bottom edge (the 1 chi mark), thus creating two intersecting diagonal lines. The two negative and positive right-angled trapezoids created by this process would thus fulfill the structural requirement of “the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top.”

“The crotch insert is 5 cun. One occupies the front left and one the back right.” These statements indicate the form of the crotch insert and the method of attaching it to the garment. Based on the description, the two diagonal lines on the rectangular piece would create an isosceles triangle measuring 5 cun at its base, just as called for by the manuscript (“the crotch insert is 5 cun”); this could then be used as the crotch insert. Since there are two ways to read the statement “One occupies the front left and one the back right,” there are likewise two possible ways of understanding the patterning of the garment. By consulting previous discoveries, one may establish that the trousers described in Making Clothes had the “open rear gate” structure.[26]

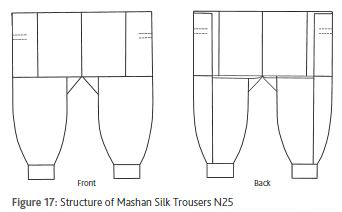

The main differences between these two methods of patterning the crotch lie in the different positions at which the crotch insert is attached. In Pattern 1, the two triangular crotch inserts are separately placed in the triangular gaps between the trouser pieces, creating a flat surface (Figure 15). In Pattern 2, the two inserts are sewn into the inner part of the crotch in the areas next to the left and right legs. Edge ba of insert 1 is sewn to edge od of the right front leg portion of the trousers, while edge ca is sewn to edge o′d′of the right rear leg portion. Edge b′a′ of triangular insert 2 is sewn to edge oe of the left front leg portion, and edge c′a′ of the same insert is sewn to edge o′e′ of the left rear leg portion. Edge bc of insert 1 and edge b′c′of insert 2 are then sewn together, producing the horizontal breadth of the crotch (Figure 16). When constructed in three dimensions, this sewing method thus provides substantial space in the crotch area of the garment, improving comfort for the wearer and facilitating movement of the legs. We are relatively inclined to think that Pattern 2 is more likely to have existed.[27] Real examples of the use of inserts to provide more space in a garment in order to improve its fit can be seen among the clothes recovered from Mashan Chu Tomb M1; for example, a large-sleeved gown, a broad-sleeved gown and a pair of silk trousers all incorporate inserts (in either the underarm or the crotch area).[28]

(B) Comparison With the Silk Trousers From Mashan Chu Tomb M1

Mashan Chu Tomb M1 yielded a pair of silk trousers with item number N25 (hereafter called “Mashan Silk Trousers N25”), consisting of a waist portion and a leg portion (Figure 17). The waist portion is composed of four pieces of grayish-white silk, with each leg of the trousers connected to two waist pieces; each one measuring 30.5 cm wide and 45 cm long. The leg portion consists of four pieces of fabric, two for each leg. One piece of each pair comprised a full standard bolt of silk, measuring 50 cm wide and 61 cm long; the other consisted of half a bolt, measuring 25 cm wide and 59 cm long. A rectangular crotch piece measuring 12 cm long and 10 cm wide was inserted and connected to one side of the upper part of the leg portion of the garment. One wide edge was sewn to the waist, while one long edge was sewn onto the leg portion. Folded, this produced a triangle shape; opened, it created a funnel shape. The two crotch portions of this pair of trousers were not connected; the upper part of the leg portion was connected to the waist portion, and the rear part of the waist was left wide open, forming an open crotch.[29]

Compared with the Mashan Silk Trousers N25, the Making Clothes trousers are relatively close in form to modern pants. The latter form an “A” shape and were produced using the jiaoyu method, while the Mashan trousers form an “H” shape and include only pieces cut along the grain. The crotch inserts of the Making Clothes trousers consist of two isosceles triangles stitched together to form a rhomboid, creating a closed structure; the crotch inserts of Mashan Silk Trousers N25, by contrast, consist of two separate, unlinked rectangles. Both of these crotch insert methods increase the amount of room in the front and rear of the garment in order to provide comfort for the wearer. The Making Clothes trousers provide a more secure seal than the Mashan trousers and could have been used directly as outerwear. They seem to have been meant for use together with the clothing type xi [袭] mentioned in Making Clothes, constituting the so-called “trousers and robe outfit” [kuzhe fu 袴褶服]. Mashan Silk Trousers N25, with its open rear waist, was worn by the tomb occupant next to the skin with an additional dark-brown plain silk skirt outside it,[30] as would suit a foundation garment. The many pairs of aristocratic women’s trousers unearthed from the Southern Song dynasty tomb of Huang Sheng all have an “A” shape. This outline is well suited to the natural morphology of the human body, with its gradual increase in size from waist to hip.[31] A pair of men’s trousers recovered from the Ming dynasty tomb of Zhang Mao and his wife likewise exhibit an “A” shape, narrow at the top and wider at the base, as well as a linked-crotch structure.[32] The influence of trousers of the Making Clothes type seems obvious.

The Qin manner of wearing trousers is visible on many of the terracotta warriors of Emperor Shihuangdi’s mausoleum complex. A chariot attendant figure from Pottery Warriors and Horses Pit 2 was placed to the left of a war chariot. It wears a war gown reaching down to its knees underneath a cuirass, and the trouser legs that emerge from beneath the gown appear finished and well fitted (Figure 18). Locus II of Bronze Birds and Pottery Musicians Pit K0007 contained a boatman figurine with both legs extended and body bent forward in a seated rowing position; its trousers are also in a narrow, fitted style (Figure 19).

MAKING CLOTHES AND QIN STANDARDS FOR FABRIC

The patterns for skirts and trousers described in Making Clothes all use components of regular sizes. The large diagonal-cut skirt, for example, calls for pieces measuring 5 cun, 1 chi, 1 chi 5 cun, and 2 chi; the medium version uses 5 cun, 1 chi and 1 chi 5 cun; the small version uses components sized 5 cun, 5 cun and 1 chi. The trouser pattern calls for components measuring 1chi and 5 cun. These values are all multiples of 5 cun; the designs clearly rely on the standard Qin dynasty fabric width of 2chi 5 cun. Would the patterns in Making Clothes be suitable for use with different dimensions of fabric? Taking the measurement of 2chi 2cun, used in the territory of Chu, as an example,[33] let us examine the matter further.

First, the skirt patterns: Based on the measurement data for the large diagonal-cut skirt in Making Clothes, a complete bolt of fabric, after the diagonal cuts were made, would yield number groupings of 5cun with 1chi 7cun; 1chi with 1chi 2cun; 1chi 5cun with 7cun; and 2chi with 2cun. The eight right-angled trapezoids of fabric produced by the cutting process would come in matching pairs that fit together top to bottom. When the pieces were assembled, four of them would have to be flipped over and installed with the reverse side up. However, if a bolt width of 2chi 5cun was used, then four of the resulting trapezoidal pieces would share the same dimensions, and pairs of the pattern pieces could be switched, making the assembly process more flexible and thereby avoiding the unfortunate need to use the reverse side of the fabric. The same situation with the reverse of the fabric would appear in the process of assembling the medium skirt. If made with a width of 2chi 2cun wide, the waistlines and hemlines of the large, medium and small skirts would all be reduced to varying degrees. The waist circumference of the large skirt would measure only 3chi 2cun (approximately 74 cm),[34] and the waist figures for the large and medium skirts would then be equal, while the small skirt would lose the relaxed, open style of construction that results from a bolt 2chi 5cun wide. Clearly, several problems would arise when following the Making Clothes tailoring methods with a bolt of 2chi 2cun. If one did not adhere rigidly to the Making Clothes measurements, but simply imitated the text’s design logic (choosing regular values convenient for use and calculation), then what kind of results could one achieve by tailoring the garments with 2-chi 2-cun fabric? Suppose one adjusted the measurements used as follows: for the large skirt, the first measured at 2 cun, the next at 1 chi, the next at 1 chi 2cun, and the next at 2 chi; for the medium skirt, the first measured at 2 cun, the next at 1 chi, and the next at 1 chi 2cun; and for the small skirt, measuring the first at 2 cun, the next at 2 cun, and the next at 1 chi. Through calculations and deduction, one can see that the waist and hem circumferences of all three skirt types would clearly be smaller, and the large and small versions would still have the same waist measurement, amounting to only 3chi 2cun (approximately 74 cm); and the waist circumference of the small skirt would shrink to as small as 1chi 6cun (approximately 36.96 cm), leaving the skirt waist too small for any adult to wear.

Now let us examine the tailoring of trousers. If one used fabric bolts with a width of 2chi 2cun and followed the three-part measuring instructions in Making Clothes, the measurements in the structure of the trousers would be adjusted to 1 chi 2 cun. Although this could satisfy the need for two right-angled trapezoids with “the top being the bottom and the bottom being the top,” the width of the triangular insert at the bottom hem would be only 2cun. If we then excluded the sewing ends, there would hardly be much width left for the triangle insert. This would obviously not be the intention of the original design. In addition, for a pair of trousers made based on a 2chi 2cun fabric width, the hip measurement would have been too small (only about 92 cm), and would not allow sufficient slack to be worn.

Based on the above, it is evident that the tailoring methods depicted in Making Clothes were closely related to the width of fabric used and had been designed specifically for use with a bolt of fabric measuring 2chi 5cun wide. Qin regulations specify: “The length of the cloth is 8 chi. The width of the cloth is 2 chi 5 cun. If the length is bad, or should the width not be as specified, it will not do.” These measurements of 8chi long by 2chi 5cun wide specify the dimensions of “one bolt” [yi bu 一布] of fabric. Qin law specifies that “one bolt” is worth eleven qian-coins,[35] thus establishing a base-11 currency system. Evidently, the measurement of 2chi 5cun was established as a standard width for fabric under Qin; its importance in economic activities is quite clear. The tailoring techniques described in Making Clothes rely on this very standard, and the resulting garments certainly showed Qin cultural characteristics. Due to the brevity of the Qin reign, the Making Clothes techniques, with their dependence on the 2chi 5cun figure, apparently were not broadly implemented. They ceased after the implementation of 2chi 2cun as a standard fabric width, as recorded in the Statutes and Ordinances of the Second Year manuscript from the Western Han dynasty.[36]

References Cited

- Liu, Li 刘丽. 2015. “Beida cang Qin jian ‘Zhiyi’jianjie” 北大藏秦简〈制衣〉简介 (A Brief Introduction to Making Clothes on the Qin Slips in the Collection of Peking University). Beijing daxue xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) 北京大学学报(哲学社会科学版) (Journal of Peking University [Philosophy and Social Sciences]) No. 2.

Liu, Li刘丽2015. “Qiantan shanggu fuzhuang de xiecai fa” 浅谈上古服装的斜裁法 (A Simple Discussion of the Diagonal Cutting Method for Ancient Clothing). In Chutu wenxian yanjiu 出土文献研究 (Studies of Unearthed Literature), Vol.14. Zhongxi shuju, Shanghai.

All the materials quoted from Making Clothes in this article, as well as Li Liu’s assessments, are drawn from the above two articles; they will not be otherwise noted. - Peking University Institute of Unearthed Texts 北京大学出土文献研究所. 2012. “Beijing daxue cang Qin jiandu gaishu” 北京大学藏秦简牍概述 (A General Description of the Qin Slips and Tablets in the Collection of Peking University). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) No. 6.

Peking University Institute of Unearthed Texts 北京大学出土文献研究所. 2012. “Beijing daxue cang Qin jiandu shinei fajue qingli jianbao” 北京大学藏秦简牍室内发掘清理简报 (The Indoor Excavation of the Qin Slips and Tablets in the Collection of Peking University). Wenwu 文物 (Cultural Relics) No. 6. A Carbon-14 assessment of the PKU Qin slips assigns them to 2,345 plus or minus 35 years BP (with a reference date of 1950), a fairly early date. - Collation Group for the Bamboo Slips Unearthed From the Qin Tombs at Shuihudi 睡虎地秦墓竹简整理小组. 1990. Shuihudi Qin mu zhujian 睡虎地秦墓竹简 (The Bamboo Slips Unearthed From the Qin Tombs at Shuihudi), annotation and notes, p. 36. Wenwu chubanshe, Beijing. “Jinbu lü” 金布律 (Statutes on Currency and Fabrics) in the Qinlü shibazhong 秦律十八种 (Eighteen Varieties of Qin Statutes), slip 66 states: “The length of the cloth is 8 chi. The width of the cloth is 2 chi 5 cun. If the length is bad, or should the width not be as specified, it will not do.”

- Chen, Wei 陳偉 (editor). 2014. Qin jiandu heji (yi) 秦簡牍合集 (Collected Qin Manuscripts), Vol. 1, pp. 41-42. Wuhan daxue chubanshe, Wuhan.

- Ruan Yuan 阮元 (Qing dynasty) (editor). 1982 (reprint). Mengzi zhushu 孟子注疏 (Annotations and Commentaries of Mencius). In Shisanjing zhushu 十三經注疏 (Annotations and Commentaries of the Thirteen Classics), p. 2667. Zhonghua shuju, Beijing.制 [zhi] may be understood as 作 [zuo], “to make.” In the “Liang Huiwang shang” 梁惠王上 (King Hui of Liang Part One) chapter in Mengzi 孟子 (Mencius), it contains the phrase “may be made to produce clubs” [可使制梃], and the Zhao Qi commentary specifies, “制 is 作.”

Ban Gu 班固 (Han dynasty). 1962 (reprint). “Liyue zhi” 禮樂志 (Treatise on Ritual and Music). In Hanshu 漢書 (History of the Han), p. 1029. Zhonghua shuju, Beijing.述 [shu] here means “to recount” or “to follow along with.” This text reads: “述 has the meaning of 明 [ming, brilliant, to illuminate], and the Yan Shigu commentary notes, “述 means to discern the meaning of something and follow it.”

Xu Zhaoqing 徐昭慶 and Mei Dingzuo 梅鼎祚 (Ming dynasty) (editors). Kaogongji tong 考工記通 (Records of Examination of Craftsman), Vol. 1, pp. 6-7. Hua’e Hall edition. This textin the Zhouli 周禮 (The Rites of Zhou) states: “The learned invent an object, and the clever describe it and maintain it through the generations, calling it ‘craft’ [gong 工].” The Xu Zhaoqing edition notes, “述 [shu] means to take the model of something for posterity.” - Yu, Jiaxi 余嘉錫. 1985. Gushu tongli 古書通例 (Comprehensive Examples From Ancient Books), pp. 19-20. Shanghai guji chubanshe, Shanghai. This source states: “Of old, when people wrote books, they did not sign their own names. Teachings were passed down from teacher to teacher, and authors knew from whom their learning came, later writing it down in order to raise it up.” “Some came from the hand of the teacher; some were first committed to bamboo and silk by disciples; some were added to by later teachers, but were able to retain the model qualities of their school, and hence were still called the learning of a certain teacher.”

- Xu Shen 許慎 (Han dynasty). 2006 (reprint). Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 (Explaining and Analyzing Characters), p. 159. Zhonghua shuju, Beijing.

- Xu Shen 許慎 (Han dynasty). 1983 (reprint). Duan Yucai 段玉裁 (Qing dynasty) (commentator). Shuowen jiezi zhu 說文解字注 (A Commentary on Explaining and Analyzing Characters), p. 358.Shanghai guji chubanshe, Shanghai.

- See 8., p. 396.

- See 8., p. 393.

- Ban Gu 班固 (Han dynasty). 1962 (reprint). “Kuai Wu Jiang Xifu zhuan” 蒯伍江息夫傳 (Biographies of Kuai Wu and Jiang Xifu). In Hanshu 漢書 (History of the Han), p. 2176. Zhonghua shuju, Beijing.

- In “diagonal cutting,” the directions of the cut and the grain of the fabric form the cutting angle; whereas in a straight-cut garment, the direction of the cut and the grain of the fabric are the same, so that the cutting angle is zero degrees.

- The phrase “上为下,下为上” is in fact written in the manuscript as “上为下=为上.” In our explications here and below, the character duplication mark [=] has been written out as the duplicate character.

- Making Clothes explains that “The length follows that of the person,” which means the length of the garment should be tailored to suit the needs of the wearer. For convenience’s sake, the diagram assumes a length of 3 chi 6 cun. The arrow in the diagram indicates the direction of the warp of the fabric.

- All four cases shown in the diagram assume a seam allowance of 1 cun on the left and right sides of each individual piece.

- Ancient skirts often had an open, fan-shaped structure requiring that a waistband be added; when the skirt piece was used to cover the body, a long, narrow waistband was wrapped around the body in order to hold it in place. Concerning the style of ancient skirts, one can consult women’s Skirt N17-3 from Mashan Chu Tomb M1 as well as women’s Skirt 329-1 from Mawangdui Han tomb M1. When a large diagonal-cut skirt following pattern 3 was worn, the belt of the skirt would have been pulled straight horizontally and wrapped around the edge of the waist. Vertical waves would then have formed in the body of the skirt.

- Qiu, Guangming 丘光明 et al. 2001. “Duliangheng juan” 度量衡卷 (Weights and Measures). In Zhongguo kexue jishu shi 中国科学技术史 (History of Science and Technology in China), p. 168. Kexue chubanshe, Beijing.

- Ruan Yuan 阮元 (Qing dynasty) (editor). 1982 (reprint). Liji zhushu 禮記注疏 (Annotations and Commentaries of the Book of Rites). In Shisanjing zhushu 十三經注疏 (Annotations and Commentaries of the Thirteen Classics), p. 1477. Zhonghua shuju, Beijing. “Yuzao” 玉藻 (The Jade-Bead Pendants of the Royal Cap), a chapter of the Liji 禮記 (Book of Rites), states: “That casual gown at the waist was thrice the width of the sleeve; and at the bottom twice as wide as at the waist.” [English translation quoted from Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 28, Part 4: The Li Ki, trans. James Legge, 1885, Oxford: Clarendon Press. – Trans.] The subcommentary of Kong Yingda notes, “Qi [齐] refers to the bottom edge of the garment, while yao [要] refers to the top edge. The text says that one should tailor the width of the bottom edge to double that of the middle of the waist.”

- Jingzhou Museum of Hubei Province 湖北省荆州地区博物馆. 1985. Jiangling Mashan yi hao Chu mu 江陵马山一号楚墓 (Chu Tomb M1 at the Mashan Site, Jiangling County), pp. 20, 23. Wenwu chubanshe, Beijing.

Hubei Provincial Museum 湖南省博物馆 et al.(editors). 1973. Changsha Mawangdui yi hao Han mu 长沙马王堆一号汉墓 (Han Tomb M1 at the Mawangdui Site, Changsha City), Vol. 1, p. 69. Wenwu chubanshe, Beijing. - See [19], Jingzhou Museum of Hubei Province.

- See [19], Hubei Provincial Museum.

- The materials of Emperor Shihuangdi of the Qin empire’s terracotta army used in this paper are all currently in the collection of the Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum.

- Figurine Y19 from the acrobatic performances is relatively tall and solid, and the skirt it wears is correspondingly rather large; thus the selection of the “strongly curved waistline” version of the large diagonal-cut skirt is quite appropriate. The human figurine Y4 is slim, with a relatively narrow waist; thus the “gently curved waistline” version of the medium diagonal-cut skirt is suitable. Since the waist measurement of the small diagonal-cut skirt was extremely narrow, a small amount of activity in that garment was likely to expose the lower body; and since the garment was worn alone, without any overskirt, this precludes the possibility that the small diagonal-cut skirt was used.

- See [8], p. 654.

- See [3], “Rishu” 日书 (Daybook) annotation and notes, p. 227. Type A, slip 153 verso.

- See [20], p. 23. The trousers from the Mashan Chu Tomb M1 were designed with an open back, a classic characteristic of trousers in early China; thus the trousers in the Making Clothes Qin manuscript were arranged with a rear-opening structure.

- This sort of patterning method with inserts would give the trousers a short rise, but by linking up with the wide head of the waist above, one could add depth to the rise, thereby reaching a suitable fit.

- See [20] above.

- See [20], p. 23.

- See [20], p. 17.

- Fujian Museum 福建省博物馆 [now 福建博物院]. 1982. Fuzhou Nan Song Huang Sheng mu 福州南宋黄昇墓 (The Southern Song Tomb of Huang Sheng in Fuzhou City), p. 14. Wenwu chubanshe, Beijing.

- Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology 湖北省文物考古研究所. 2007. Zhang Mao fufu hezang mu 张懋夫妇合葬墓 (The Husband and Wife Joint Tomb of Zhang Mao), p. 18. Kexue chubanshe, Beijing.

- Peng, Hao 彭浩. 1996. Chu ren de fangzhi yu fushi 楚人的纺织与服饰 (Textiles and Clothing of the Chu People), p. 39. Hubei jiaoyu chubanshe, Wuhan.

- These measurements are net measurements excluding a seam allowance of 1 cun on each edge.

- See [3], p. 36. Slip 67 states: “Eleven qian-coins is equivalent to one bolt of cloth. In coming and going, qian-coins may be taken as equivalent to metal and cloth according to the statutes. Fine thread, plain white thread, crimson thread, cloth, (fine silk gauze), and quanlou-fine cloth need not follow this statute.”

- Editorial Group for the Bamboo Slips From Han Tomb M247 at the Zhangjiashan Site 張家山二四七號漢墓竹簡整理小組. 2006. Zhangjiashan Han mu zhujian (er si qi hao mu) (shiwen xiuding ben) 張家山漢墓竹簡: 二四七號墓 (釋文修訂本) (Bamboo Slips From the Han Tombs at the Zhangjiashan Site: Tomb M247 [Revised Transcription]), p. 44. Wenwu chubanshe, Beijing. Slips 258-259 of the “Ernian lüling” 二年律令 (Statutes and Ordinances of the Second Year) state: “With respect to the sale of silk cloth, if the bolt does not reach a full width of 2 chi, do not take it. If it can be confiscated and reported, then use it as confirmation.”

Wenwu (Cultural Relics) Editor: Ran Wu

Translated by Dr. Paul Nicholas Vogt, Assistant Professor of Early Chinese History, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, School of Global and International Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA

This article was originally published as “Beijing daxue cang Qindai jiandu Zhiyi de ‘qun’ yu ‘ku’ ” 北京大学藏秦代简牍《制衣》的“裙”与“袴” in Wenwu (Cultural Relics) No. 9, 2016, pp. 73-87.